The History Of The Dual-Clutch Transmission

In the beginning, man invented the engine. Now, the engine was shift-less and isolated. And as inventors hovered over the surface of their workshops, they moved upon the crankshaft and said, "Let there be a transmission to bring the engine's power to the driveshaft." They added a clutch and saw that it was good. Then, people wanted to drive really fast without removing their hands from the wheel, so we got dual-clutch transmissions (DCTs), launch control, and Ferrari 812 Superfasts that can hit 60 miles per hour in less than three seconds.

That's a bit of an oversimplification, but the point is that transferring constant rotational energy to a wheel that sometimes needs to not move is crucial. Clutches decouple engines from gearboxes to allow such non-movement, but operating a single clutch and an H-pattern manual transmission with no synchronizers takes skill, finesse, and elbow grease. Inventors and engineers in the early days of cars did their darndest to make easy-to-operate gearboxes, such as Sturtevant's automatic transmission from the early 1900s and the pre-selector gearbox from the 1930s. But DCTs are in another universe of complexity.

DCTs work by giving even-numbered gears a clutch and odd-numbered gears a separate clutch, then letting hydraulics and electronics sort out the power flow. The result is smooth, uninterrupted acceleration and improved fuel economy without the high skill and effort ceiling. And though the electronic controls we take for granted didn't exist in the early 20th century, inventors still tried to make the concept work.

Early dual-clutch efforts: 1910 to the 1940s

You'll sometimes hear that the 1910 Morgan three-wheeler used two clutches, but they're dog clutches, which are different from friction clutches, and the transmission isn't a dual-clutch in the modern sense. Dog clutches feature in the appropriately-named high-performance dog box transmission, and involve interlocking jaws to transmit power. It's as solid a connection as possible without welding the shafts together. In addition to dog clutches, the Morgan also featured a leather-faced main cone clutch. Of course it's leather, this is Morgan. Its cars still use wooden frames, after all.

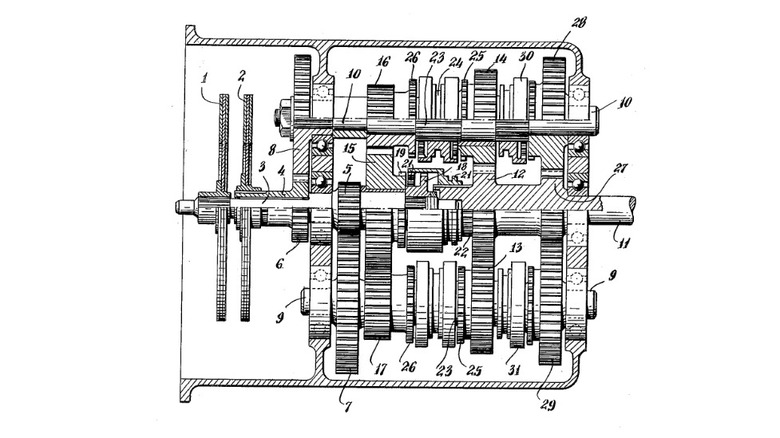

In 1935, French inventor Adolphe Kégresse patented a bona fide "dual-clutch transmission." He thought manual transmissions were too dang hard to use, and wanted a simpler, smoother alternative. In 1939, Kégresse fitted a prototype dual-clutch called Autoserve into a Citroën Traction Avant, but it never reached production. His invention was also patented in America in 1946 (US2543412A), likely by his son, also named Adolphe, as the patent states it was filed by "Adolphe Valentin Kégresse, Administrator of the Estate of Adolphe Kégresse, Deceased." The elder Kégresse had passed away in 1943.

Borg-Warner patented its "dual countershaft transmission" in 1949 (US2599801A), which intended to "provide a means for operating a transmission in which an uninterrupted flow of power from the engine is applied through the transmission during speed changes." In addition to the two friction clutches, Borg-Warner's design used five dog clutches (positive clutches) to engage gears.

Dual-clutch dormancy and resurgence: late 1930s through the 1980s

Unfortunately for Kégresse's DCT, 1939 is the same year that Oldsmobile offered the torque-converter Hydra-Matic transmission for sale in its new 1940 models. This automatic knew when to change gears so drivers didn't have to, providing the laziest way possible to get from point A to point B. Okay, it's easier on people who can't shift due to injuries and illness — we'll grant that. As for Borg-Warner's "double countershaft transmission," as far as we can tell, none were built and the patent expired in 1969.

Speaking of the 1960s, this is where we get to Porsche. In 1964, the company began dabbling with dual-clutch technology, and wanted to feature such a gearbox in the Porsche 911. Well, electronic controls still weren't smart enough, even though Jack Kilby had invented microchips back in 1958. So, Porsche wisely made the 911 manual-only forever. We're kidding — sadly, the company instead offered its torque-converter four-speed Sportomatic as a 911 option, which did the impossible and made Porsche 911s boring.

But, Porsche is still Porsche, and if there's cool tech to be explored, it will be. So, in 1979, the automaker revisited the dual-clutch concept for its 956 Group C racecar. By 1981, the dual-clutch was undergoing testing to give drivers smooth, uninterrupted power delivery — a must for the powerful turbo cars to avoid drops in boost. Porsche dubbed it the barely pronounceable "Doppelkupplungsgetriebe," which thankfully was shortened to PDK.

Dual-clutch racing revolution: the 1980s

Porsche's PDK saw racetrack use in Monza in 1986 in the 956's successor, the Porsche 962, and its ability to decrease lap times was immediately apparent. At first, the transmission was operated much like a sequential manual that changed gears via a lever moving forward or backward. Then came the real game changer: Porsche moved the controls to the steering wheel. Hans Stuck, Formula One driver and one of the drivers of the Porsche 962 at Le Mans, spoke of the PDK in glowing terms, telling Hagerty that "it was wonderful because you could concentrate on driving, keeping your hands on the wheel."

To switch gears, there were two buttons. The top one upshifted and the bottom one downshifted. Finally, drivers could keep both hands on the wheel through corners while shifting. Porsche also tested PDKs in a 924 and a 944, but used the push/pull lever instead of buttons. As you can tell, there aren't any 924s or 944s running around with such PDKs, so it never made it into production. But, one of the people who got to test the cars was the legendary Ferdinand Piëch, then head of technical development at Audi.

Piëch was smitten, and instantly rushed back to Audi, telling the team they needed to put this transmission into the Group B Audi S1 right dang now. In November 1985, a PDK-equipped Audi Quattro S1 crushed competitors with a 19-minute lead at the Semperit Rally Austria.

Dual-clutch popular adoption: the 2000s

Racing tech takes time to trickle down. Manufacturers must make sure a feature is a viable money-maker before they're willing to cram said feature into a sedan. And though the PDK was killing it on racetracks, there wasn't much need for it on the street, so it went dormant. Porsche's 962 enjoyed its final race in 1993 at Road America, though Dauer made a street-legal 962 for racing in the 1994 Le Mans GT1 category.

In 2003, somehow, DCTs returned — this time for the masses, as Europe got the Volkswagen Golf R32 with the first production dual-clutch, followed soon after by the Audi TT. Let's see, who was CEO of Volkswagen in the early 2000s? Ah, Ferdinand Piëch, that makes sense. Volkswagen called its DCT the "DSG," which stands for DirektSchaltGetriebe. Thank goodness German manufacturers like acronyms because that's a mouthful. S-Tronic is Audi's term. Audi, does the S stand for "Schnelles und Automatisches Schalten über Schaltwippen und Zwei Kupplungen" (swiftly and automatically shifting via paddles and two clutches)?

And so, before the manual transmission was a protected species, DCTs exploded in popularity. This is especially true in performance cars where the consistent power delivery ensured phenomenal acceleration numbers, which is why we have DCTs in the R35 Nissan GT-R, Audi R8, internal combustion Porsches since 2008, and the glorious Bugatti Veyron.

Dual-clutch waning popularity: today

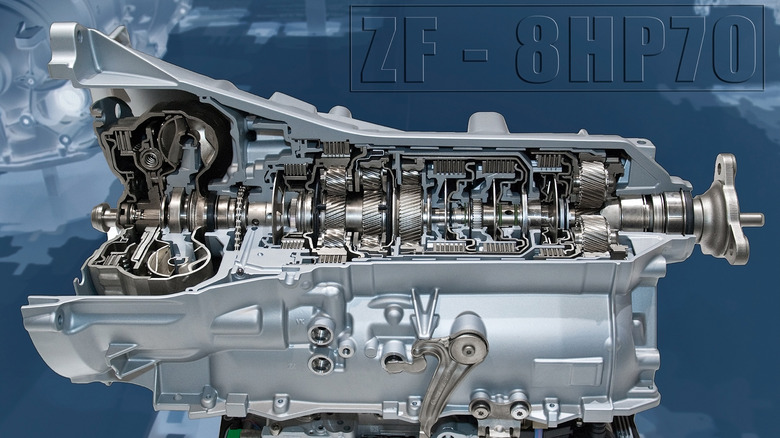

Things change, though. Some automakers are loath to admit it, but dual-clutch transmissions have serious disadvantages. Aston Martin and BMW have both abandoned DCTs and embraced torque converter automatics like the ZF 8HP. In 2018, Aston Martin's CEO even predicted DCTs would eventually disappear. You see, DCTs are complex, expensive, relatively heavy, and don't like creeping forward. Plus, contrary to their whole well-advertised deal, shifts can actually be pretty harsh if you go from insane, edge-of-the-envelope driving back to a sedate pace.

Another threat to DCTs is electrification, as most EVs just use direct drive, with the Porsche Taycan and its two-speed transmission being a rare exception. Enthusiasts have also begun to miss stick-shifts regardless of acceleration times, and pine for that mechanical connection that went away with, as Jeremy Clarkson once joked, flappy paddles. But while DCTs may have taken a ding in widespread favor, they're not remotely extinct.

At Porsche, the PDK is sticking around, and in 2022, over 75% of 911 buyers chose that gearbox. Christian Hauck, head of Alternative Drives at Porsche, told Hagerty, "one very important thing for us is that we have the possibility to change gear ratios on every single gear that we are having in the gearbox, so we can really make it suitable in the perfect way to every car that we apply the PDK transmission to." Dual-clutches are indeed technologically marvelous, and whatever their weaknesses, at least they aren't CVTs.