10 Of The Strangest Boeing Aircraft Ever Made

Boeing is one of the biggest and oldest manufacturers of large airframes, and some of its planes are pretty odd. People associate it with well-known commercial airliners like the 737, the 767, and the regal 747, the "Queen of the Skies," which went out of production in 2023 after 54 years. Yet Boeing has been building large aircraft since the early days of aviation, including the 70-passenger 314 Clipper flying boat that first flew in 1938, as well as famous combat planes like the B-17 Flying Fortress and the legendary B-52 bomber.

Boeing's long expertise in building large aircraft helps to make its planes ideal test beds for experimental or special-duty planes. For instance, many of its jets, including the 747, are four-engine models, which makes them excellent for testing new engines, since the extra engines offer redundancy if a test engine fails. Boeing even built a shortened, stubby 747SP model for special projects.

One of the most famous oddball Boeings is Air Force One, with its iconic livery created by car designer Raymond Loewy. Yet this jet looks relatively normal compared to some of the most striking special-purpose Boeings. From extra engines to wild-looking fuselages to gigantic radar dishes, here are ten of the strangest Boeings ever made.

Boeing 377 Stratocruiser

Our first offbeat Boeing actually served for years as a passenger airliner, albeit a rare one, as only 56 were built: the 377 Stratocruiser. Of those 56 aircraft, no fewer than nine crashed. Not a great safety record, to say the least. Pan Am alone lost seven of them in just seven years of operation in the 1950s. Ironically, it was Pan Am's desire for a long-range passenger airliner to compete with TWA's Lockheed Constellation that led Boeing to build the Stratocruiser in the first place.

The resulting aircraft sported a strange, bulbous, double fuselage that looked as if the top half of one plane had been grafted onto the bottom of another plane. This created a two-deck configuration with a downstairs lounge accessed by stairs — the opposite of the upstairs lounge that would later appear on the 747. This strange configuration flew in the face of aeronautical design principles in the 1940s, which called for narrow fuselages supported by large wings.

Yet it wasn't aerodynamics that led to the Stratocruiser's abysmal safety record, but rather its propellers. Its hollow-core propellers had an unfortunate tendency to disintegrate in flight. Even successful long-haul flights to Hawai'i tended to arrive on two or three out of four engines. One flight didn't quite make it, ditching on two engines in front of the Coast Guard ship Pontchartrain; all passengers were rescued.

Boeing YC-14

The Boeing YC-14 looked strange from any angle. Its tall, narrow fuselage was odd by itself, but the plane's twin jet engines were mounted above its wings, which were already at the top of the plane, putting the engines almost comically high up, and close in to the fuselage, to boot. The result, when viewed from the front, almost looked like a plane wearing Mickey Mouse ears. Or perhaps shoulder cannons, if your taste in animation runs more toward manga than Disney.

They weren't ears or cannons, though: they were GE CF6-50D turbofan jet engines, and there was a reason they were mounted in such an odd configuration. In the 1970s, the U.S. Air Force sought a replacement for the C-130 Hercules cargo plane, and the specs called for a short takeoff and landing (STOL) aircraft. The YC-14's over-wing engine design took advantage of a phenomenon known as the Coandă effect, in which engine exhaust flowed over the top of the wing and deflected downward, generating extra lift and enabling shorter takeoffs.

This allowed the YC-14 to take off in as little as 800 feet at speeds as low as 68 mph. Yet it could carry up to 25 tons of freight. Plus, its climb rate of 6,000 feet per minute vastly exceeded the C-130's. The jet also employed cutting-edge technologies, such as flight controls connected to fiber optic cables, a system called fly-by-light. Yet the Air Force's shifting priorities led to the YC-14's cancellation, with only two prototypes ever being built.

Boeing Dreamlifter

The Boeing Dreamlifter looks a bit like a 747 that did too many steroids. From just aft of the cockpit to just before the tail rudder, the fuselage bulges like a hot dog roll, with the nose and tail of the plane as the hot dog. It looks bulky and awkward and doesn't seem like it should get off the ground, but this plane not only flies, it carries big chunks of other planes in its oversized cargo hold. Its size makes it one of the biggest planes ever made.

This converted 747-400 was built during the 2000s decade to transport large aircraft segments between Boeing's manufacturing centers worldwide. It can carry components as large as fuselage sections and wings in its immense cargo hold, which is three times the size of the hold in a standard 747 cargo plane. Its payload capacity is 47 tons.

There are four Dreamlifters, all operated by Atlas Air under a contract with Boeing. The planes have been a godsend for Boeing, cutting delivery times for some aircraft parts from a month to just a day. They're currently used for transporting 787 Dreamliner parts from factories around the world to Boeing's assembly plant in South Carolina.

Boeing E-3 Sentry

The E-3 Sentry is based on a Boeing 707-320 and is instantly recognizable via the enormous radar dome sprouting from its back like a rotating mushroom. This jet is a type of plane known as an AWACS, or airborne warning and control system, which explains the huge radar. Two struts hold up the 30-foot dome, which offers 250 miles of radar coverage in all directions, including up and down, giving the E-3 a complete view of the battlespace across 500 miles of airspace from the ground to the stratosphere.

To give a sense of the E-3's capabilities, that 500-mile view would extend from Philadelphia to Boston. Within this range, it can track up to 600 targets, and its eye-in-the-sky perspective reveals low-flying aircraft and missiles that would be invisible to ground-based radar. It can direct fighter jets to the enemy and relay data to naval and ground units. This makes it vital in an active battlespace. It also provides surveillance and reconnaissance, as well as serving as mobile air traffic control.

However, E-3 airframes are aging, and the 707 on which it's based hasn't been manufactured since 1978. Maintenance is a growing problem, and parts are becoming scarce. There is a replacement for Boeing's aging 707-based radar plane, and it's also being built by Boeing: the E-7 AEW&C, which stands for Airborne Early Warning and Control. This 737-based aircraft will carry on the E-3's mission for decades to come.

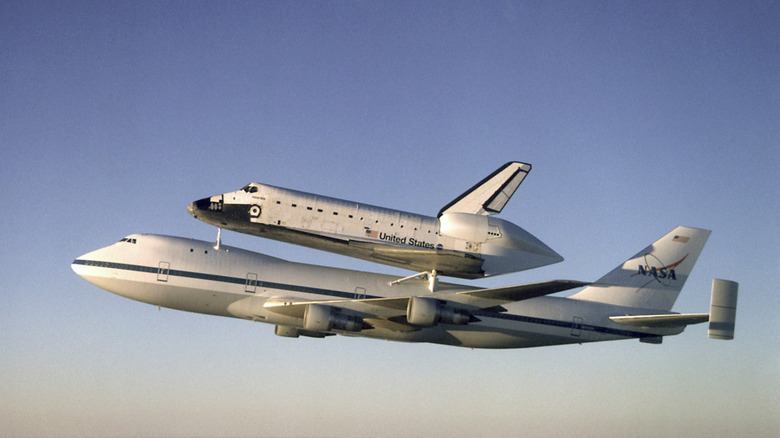

Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier

The 747's sheer size led NASA to pick a modified 747 to piggyback the Space Shuttle. There were two Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCAs), both originally commercial jets: a 747-123 and a 747-10SR-46. The Boeing was chosen over competitors like the Lockheed L-1011 due to the 747's proven heavy-lift capabilities. With the Shuttles weighing 230,000 pounds and frequently landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California, on the opposite side of the country from Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the 747's ability to ferry heavy loads over long distances was crucial.

To carry the weight of a Space Shuttle, NASA fitted external struts to the 747's fuselage along with a cradle for the spaceship to rest on. Upgraded Pratt & Whitney JT9D turbofan engines gave the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft extra thrust. Top speed when the plane and the Shuttle were mated together was only 250 knots (288 mph), far below the 747's usual top speed of about 660 mph. Enhanced avionics and flight controls helped pilots to handle the huge load.

While flight testing in 1977 validated the safety of this plane-and-Shuttle arrangement, it was still tricky to fly this slow, unaerodynamic combo, leading to restrictions on flying over populated areas and international territory. Nevertheless, pilots found that the 747s handled the stresses of low-altitude flight surprisingly well. The piggyback concept would go on to be used in other heavy transport aircraft.

YAL-1 Airborne Laser Test Bed

The YAL-1 Airborne Laser Test Bed is a 747 modified with a huge laser turret on its nose. Even without the turret, it would be odd-looking for a 747 with its matte-gray Air Force paint and complete lack of side windows on the plane's enormous flanks. But it's what lay under the gray sheet metal that made the YAL-1 truly unique, and which gave the nose's bulbous turret its deadly reach.

The system that lay in the guts of the YAL-1, the Airborne Laser Test Bed (ALTB) itself, answered the Pentagon's call for a laser weapon that could shoot down tactical and intercontinental ballistic missiles in their boost phase. The ALTB was a megawatt-class, chemical oxygen iodine laser (COIL). This was a complex system that vented chlorine and iodine exhaust gases, which then needed to be scrubbed. The nose turret alone weighed as much as 15,000 pounds and was designed both to focus the beam and to collect return images.

The COILs weighed 6,500 pounds each, and as many as six were used on the YAL-1 to generate the needed laser power. Combined with the 15,000-pound turret and other equipment such as the dorsal pod containing the Active Ranging System, it becomes apparent why the 747 was chosen to carry this immense system. In early 2010, the YAL-1 successfully shot down a test target and two test missiles, but the program was scrapped later that year.

E-4B Nightwatch

The E-4B Nightwatch, also known as the Doomsday Plane, will allow the U.S. Government to live on after a nuclear exchange or other emergency, at least in theory. All four examples of this ominously named aircraft began life as 747-200 models, which were then modified into Advanced Airborne Command Posts, intended to allow the president and other top officials to carry on their duties even while the country below them smolders in ruins. It can also support FEMA during disasters.

The E-4B's most visually distinctive feature, and the main thing distinguishing it from civilian airliners from the outside, is a hump protruding from the back of the upper deck of the 747. This houses the Milstar system, a jam-resistant satellite communication system that can reach everything from ground stations to submarines. Sharp-eyed observers will note a row of other, smaller domes and antennas running the length of the E-4B's spine and belly, all of which are for additional communications methods.

These capabilities give the E-4B its other official name, the National Airborne Operations Center, or NAOC. To support the NAOC's operation, the E-4B offers three decks with conference rooms, an operations area, a communications area, and rest facilities. The plane is hardened against electromagnetic pulses (EMPs) and nuclear blasts.

Boeing 747SP Pratt & Whitney Test Bed

The 747SP Pratt & Whitney Test Bed looks like a mutant with an extra engine nacelle growing from one side of its upper deck. Compared to the usual graceful symmetry of the 747's design, the extra engine is somewhat unsettling — a little like the three-eyed mutant fish living in the water near the Springfield Nuclear Plant in The Simpsons. But that extra engine serves an important purpose, hinted at by the plane's name.

The Pratt & Whitney Test Bed is based on the shortened 747SP, the Special Performance model we mentioned above. Pratt & Whitney, which makes engines for Boeing and Airbus, among other manufacturers, owns the only two 747SPs that are still in service. The extra engine mount on each jet allows the company to test its engines in real-life conditions. The testbed planes get plenty of use, having helped to test at least 71 developmental engines.

Pratt & Whitney's engines power aircraft across a broad range of aviation uses, from military to civilian. The Test Bed aircraft provides a platform for testing small jet engines as well as airliner engines; for instance, the company tests its BW800 engines for Gulfstream private jets. Pratt & Whitney also builds engines for firefighting and agricultural aircraft, among other industry segments.

Boeing 747SP SOFIA

When NASA looked for a plane that could carry a 106-inch reflecting telescope to altitudes as high as 45,000 feet to do observations from above much of the earth's atmosphere, the 747SP was a logical choice. The result was the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, or SOFIA, a 747 with a large retractable door in its rear fuselage that opened to reveal the telescope. The plane was a collaboration between NASA and the German Space Agency.

99 percent of the Earth's atmosphere is squeezed by gravity into its bottom few miles, and this thick layer blocks infrared observations. Additionally, most of the Earth's surface consists of oceans, where no telescopes of any sort can operate. SOFIA solves both of these problems, enabling clear infrared observations from anywhere on the planet.

SOFIA's overnight flights enabled astronomers to observe Pluto, Kuiper Belt objects, and the moons of the solar system's outer planets. SOFIA can also see infrared wavelengths that penetrate clouds of gas and dust from far regions of the galaxy, allowing it to see very distant objects that would otherwise be obscured. Unfortunately, NASA retired this 747SP in 2020, after concluding that the knowledge gained from SOFIA was no longer worth the expense of flying it.

Boeing 757 Flying Test Bed Catfish

An impish mind might look at our next plane and think of the TV show from the late 1960s called The Flying Nun, starring a young Sally Field. The Boeing 757 Flying Test Bed features a small additional wing above the flight deck, which, from some angles, resembles the nun's habit that gave Sally her improbable aerodynamics. The plane also features a modified, flattened nose, earning it the nickname "Catfish."

The nose actually comes from an F-22 Raptor fighter and contains the Raptor's AN/APG-77 active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar. The extra wing above the cockpit is equipped with the Raptor's AN/ALR-94 electronic support measures suite. The Catfish also sports the F-22's communications systems, missile warning system, and electronic warfare suite. Inside the jet is a replica of the fighter's cockpit.

All of this equipment allows Lockheed Martin's engineers to test the Raptor's systems in real time in a platform that can accommodate up to 30 engineers. Although the Raptor ceased production in 2011, the need to update its software keeps the Catfish flying regularly. The Boeing can fly with F-22s to test how the software works with other planes in formations. It can also test multiple software configurations in a single test flight.