Why Formula One Engines Went From V12s To V6s

"There are no bad ideas in a brainstorm," they say. Only slightly lesser well known is, "if there's a four stroke piston engine that's not a radial, Formula 1's tried it." There have been inline fours, sixes, and eights, 180-degree eights and 12s, V-twins, V6s, V8s, V10s, V12s, V16s, and H16s in naturally aspirated, supercharged, turbocharged, and hybrid configurations.

Most layout experimentation is ancient history, though. Let's focus on 1989+ engines, since they're likely the most familiar. The "Turbo Era" ended in 1988 when the FIA reined in horsepower to prevent repeats of the more terrifying crashes. In 1989, 1.5-liter turbo V6s were out, and 3.5-liter naturally aspirated (N/A) V12s, V10s, and V8s were in (reduced to 3.0 liters in 1995). V12s were initially popular because they rev to dental drill speeds and generate prodigous thrust, but their size and fuel consumption became burdensome. Still, Ferrari F1 V12 screams are the stuff dreams are made of.

Lighter, smaller V10s took the V12's place, but manufacturers reached for the sun with exotic materials and precision manufacturing, so the FIA melted their wings in 2006, making 2.4-liter V8s standard. This reduced development costs and emissions at first, but by 2013, the V8s were seen as outdated, thirsty engines. In 2014, regulations changed again because of F1's push toward carbon neutrality, reverting to the layout it banned in the '80s: the turbo V6. This time, however, the displacement was 1.6 liters and the powertrains became hybrids. Let's examine the progression in more detail.

Hello, V12s

Lamborghini's 3.5-liter LE3512 engine made up to 640 horsepower when it worked. In 1989, Lamborghini was owned by Chrysler, which actually had money to buy other automakers in the '80s, rather than the other way around for the last 25 years. Chrysler wanted Lamborghini to compete in motorsports, and so contracted ex-Ferrari engineer Mauro Forghieri to create a new V12 to meet the FIA's 1989 rule set. The engine won zero races.

Meanwhile, Ferrari was teething its 680-hp V12 paired with a seven-speed transmission featuring the revolutionary paddle shifting system. That transmission was a headache for Ferrari, with low battery power causing reliability woes. But, when the transmission was functioning properly and the Ferraris managed to finish a race, they ended up on the podium. As an aside, isn't it delightful that now people are manual swapping their Ferraris? Anyway, Ferrari was still running V12s in 1995, which was like making silent movies in the 1960s. In 1996, Ferrari switched to V10s.

Honda, having a V10 that provided 10 wins in 1989 and six in 1990, added a couple of cylinders for 1991 because Soichiro Honda, founder of the company, liked V12s. When your boss tells you to develop something, you do it. Besides, it made more than 650 hp and drivers such as Ayrton Senna used it to win eight races in 1991. For 1992, Honda's last year in F1 (at the time), the V12 was making 774 horsepower, but only won five races.

Formula 1 just can't make V12s work

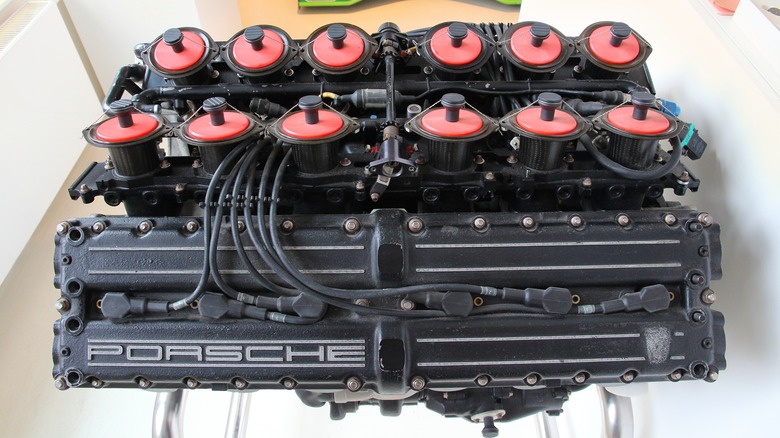

You might notice a trend. Every F1 team that felt that V12 allure started with such promise, only to realize V10s were the future. That doesn't mean companies didn't keep trying. Porsche wanted in on that sweet V12 action, putting Hans Mezger in charge of developing one. He'd created the TAG twin-turbo V6s, so surely twice the cylinders would be all-conquering. Well, the 1991 V12 was too heavy, too long, and too underpowered. Don't feel bad, Mezger went on to design other fantastic Porsche engines, including the Carrera GT's V10.

Motor Trend described Subaru's 1990 flat-12 as "the largest and ultimately least-successful design in the company's history." The flat cylinder layout had a low center of gravity, but when the engine weighs around 250 pounds more than F1's V8s and has 100 fewer horsepower than other teams' V12s, center of gravity isn't the main issue. Though it failed on the racetracks, Subaru's flat-12 did power the first Koenigsegg prototype — so that's cool.

Yamaha's OX99 V12 made 600 horsepower, which was perfect for the OX99-11 supercar it wanted to produce (it didn't). But Yamaha detuned the OX99-11 to 400 hp and wanted to charge $800,000 in 1992, hoping to create a McLaren F1-like supercar that would be highly regarded to this day (it isn't). Undeterred, Yamaha worked on the V12 to make it competitive for the Brabham team in 1991 and Jordan Grand Prix team in 1992 (it wasn't).

V10s prove 10 is a magic number

In 1993, Yamaha partnered with Judd to develop the OX10A V10, which was like if Judd's GV V10 went through The Fly's teleporter with a bolt from a Yamaha V12. In other words, it was almost identical to Judd's existing F1 V10, but its DNA contained trace amounts of Yamaha. That "new" Yamaha engine won no races, whether in Terryll or Arrows team cars.

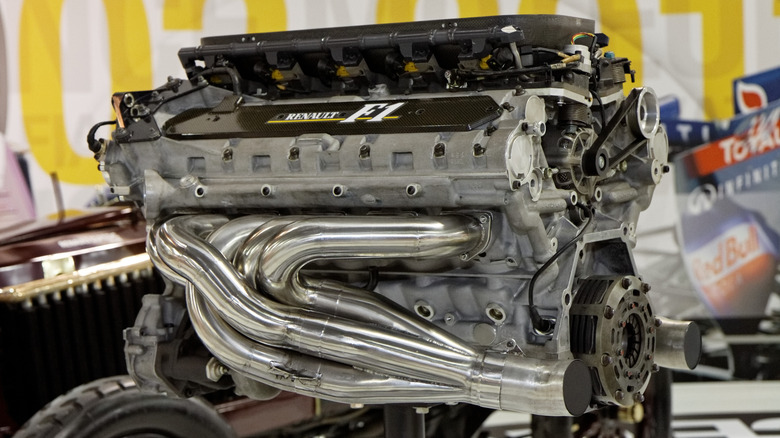

Conversely, in 1993, Renault's RS3 V10 was kicking rear ends and taking names. Of the 16 races in the 1993 season, 10 were won with the Renault V10 and the other six went to cars powered by Ford's V8. Ferrari V12 cars were firmly in third. Yamaha's V10 was dead last, and was just plain dead by 1997. At least Judd still makes V10s for Le Mans.

Though Honda's V12 was the weapon that Ayrton Senna used with McLaren's domination in 1991, Renault's V10 was the nuclear-bomb-in-a-gun-fight come 1992, with Nigel Mansel owning the season with the Williams team. V10s became the popular middle ground between the V8 and the V12, and there were plenty to choose from. Ilmor/Mercedes, Mugen Honda (started by Soichiro Honda's son, not owned by Honda Motor Company), Peugot, and Hart were all producing V10s for F1 by 1994. In 1995, the only outliers were the Ford-Cosworth V8, the Ford ECA Zetec-R V8, and the Ferrari V12. That year, Renault V10s won every race except for the Canadian Grand Prix, where a Ferrari finished first.

F1 rules: V10s drool

While Hart and Ford stuck with V8s through 1997, every car had a V10 by 1998, and so it was through 2005. While the V10s were exciting to listen to, with some revving to 20,000 rpm (intoxicatingly so), the FIA noticed engine development costs were skyrocketing and the number of manufacturers that could realistically compete were vanishingly small. In the early 2000s, there was no cap on how many engines a team could use in a season, so the engines only had to last a single race.

You might notice that F1 engines are stupefyingly expensive, so unless your team had an infinite money hose, you couldn't afford to run your engines to their limits and toss them out after one Grand Prix event. Also, manufacturers such as Mercedes-Benz were experimenting with exotic materials such as Beryllium, which is money-gobbling to use on a large scale. Oh, and it's toxic in powdered form. Again, to create a level playing field, the FIA specified that engines have only commonly available materials.

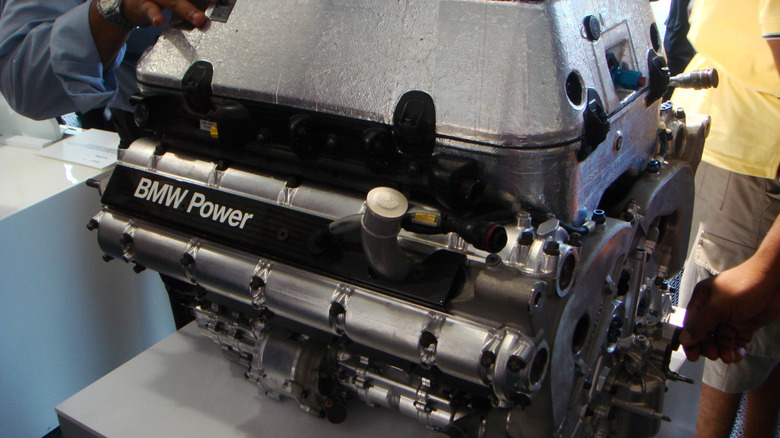

In 2006, the FIA simply mandated that F1 cars have 2.4-liter V8s, in a familiar attempt to reduce costs, make cars safer, and improve ecological friendliness. Strangely, the Toro Rosso team got to keep detuned Cosworth V10s for 2006 only thanks to a special dispensation. Fewer cylinders and smaller displacement lowered emissions, but manufacturers such as Cosworth were still able to make 20,000-rpm V8s, so the FIA capped rpms to 19,000 in 2007.

Welcome back, V6

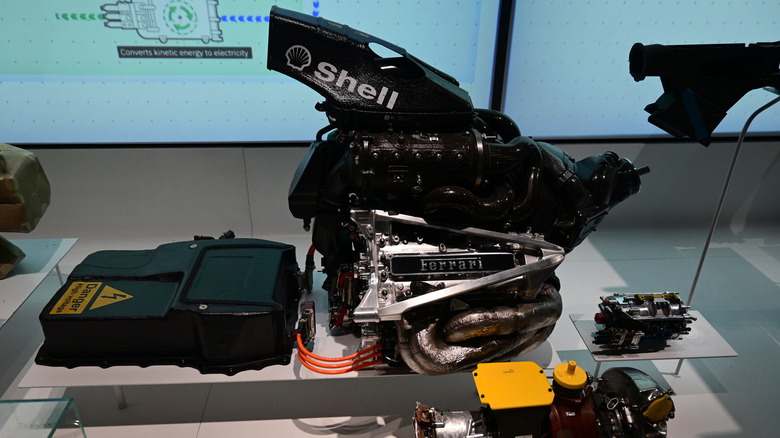

If you were a fan of the insane turbocharged V6s of the "Turbo Era" that were making up to 1,400 hp in qualifying form, the news was good in 2014. Turbo V6s were back, but of course, if you loved terrifying, edge-of-control explosive on/off powertrains with insane boost, you probably felt like audiences did when watching the Snow White or Robocop remakes. In other words, you saw a mediocre reboot of something you used to enjoy.

The turbocharged V6 "power units" crafted by Ferrari, Honda, Mercedes-AMG, and Renault use hybrid systems to make full power and are limited to 15,000 rpm, but don't think they're racing versions of a Prius or something. F1 cars produce around 1,000 hp, and driver Valtteri Bottas achieved 231 mph in 2016, the highest F1 speed ever, two years into the hybrid era. As much as F1 is trying to lower its carbon footprint, it hasn't forgotten that people still want to see the most technologically advanced, fastest cars possible.

That said, there's a reason rumors of the V10's F1 return keep reappearing. That engine is better than a middle child between V12s and V8s, it's an intoxicating instrument crafting symphonies during every race. But no matter the layouts, teams always figure out how to make the most power. If the FIA's regulations said, "engines must be seven-cylinder flatheads running kerosene," manufacturers would soon arrive at the optimal designs for peak horsepower, reliability, aerodynamics, weight, and tractability. It's the circle of life.