Air-To-Air Vs Air-To-Water Intercoolers: What's The Difference?

Forced induction engines have more power to flex over their naturally aspirated cousins. Adding forced induction is one of the few ways you can increase horsepower without doing a full engine swap. This is thanks to turbochargers or superchargers; they compress incoming air so more of it can be packed into the engine, which allows more fuel to be burned. But this extra power comes at a cost. Compressed air has a higher temperature, and so, it also has lower density. This is why the efficiency of combustion decreases as the temperature of the intake air increases. When this happens, at a certain point, the engine's control system might decide to sacrifice ignition timing and cut the power to protect itself.

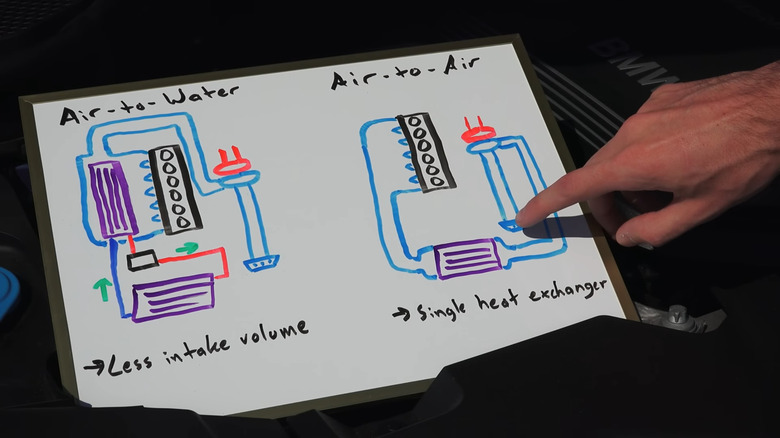

Intercoolers exist to deal with that heat before the air reaches the intake manifold, increasing its density. Cold air intakes have their pros and cons, but generally, cooler air results in a more complete combustion, granting a more consistent output of power and less emissions. There are two common designs, those being air-to-air and air-to-water. Both perform the same basic function, but how they go about doing it is different: air-to-air relies entirely on airflow while air-to-water takes advantage of liquid cooling.

How air-to-air intercoolers remove heat

An air-to-air intercooler uses ambient airflow to cool the compressed intake charge. A heat exchanger is placed in a position that allows air from the outside to easily pass through it. The compressed air from the turbocharger or supercharger enters this exchanger, where the heat is transferred from it to cooler outside air through fins before getting routed to the intake manifold. In some cases, like with this air-cooled Beetle, the hot exhaust is used to warm the cabin.

Due to the fact that these systems use a single heat transfer step, they are not prone to the compounded losses that plague more complex setups. The absence of any extra pumps or secondary heat exchangers makes it very simple from a mechanical point of view. Installation is a breeze, and it's also lightweight compared to the air-to-water system. However, mounting location matters, too. Front-mounted designs receive strong airflow but require longer charge piping, increasing system volume. Top-mounted setups shorten that distance, but they're more exposed to heat as a result.

How air-to-water intercoolers work differently

Air-to-water intercoolers remove heat using liquid coolant instead of direct airflow. The compressed intake air passes through an intercooler core where heat transfers into a circulating liquid, typically a water-based coolant. That heated coolant is then pumped through a separate heat exchanger, allowing it to relesae the heat before the fluid cycles back through the intercooler.

Water's higher heat-absorbing capacity allows these systems to extract heat efficiently with a smaller core. Because the intercooler does not need constant exposure to outside airflow, it can be mounted closer to the intake manifold. This shortens the distance the compressed air must travel and reduces overall system volume, which can improve throttle response. In some designs, the intercooler is even integrated directly into the intake manifold. Another advantage is consistency; coolant continues to circulate even when the car is idle, helping limit excess heat during stop-and-go driving or under sustained load. But that coolant needs to be changed regularly, unless you want to risk a whole other set of problems.

Heat soak, consistency, and real world driving

Heat soak describes what happens when an intercooler absorbs heat faster than it can release it. In air-to-air systems, this usually occurs at low speeds or while idle. Without sufficient fresh air moving across the core, heat accumulates and intake temperatures rise until the vehicle starts moving again.

Air-to-water systems handle this differently. As previously mentioned, coolant circulation continues in these systems regardless of vehicle speed, and radiator fans can assist with heat removal. This makes them better suited to situations involving heavy loads at low speeds, such as towing, off-road driving, or extended idling. The system's ability to store and move heat through the coolant loop helps smooth temperature swings.

That consistency comes with limits. Once the coolant itself heats up, it still needs airflow through its own heat exchanger to shed that energy. Over extended periods, coolant temperature can climb if the system is undersized or airflow is restricted. In that sense, air-to-water setups are not immune to heat soak; they simply delay it.