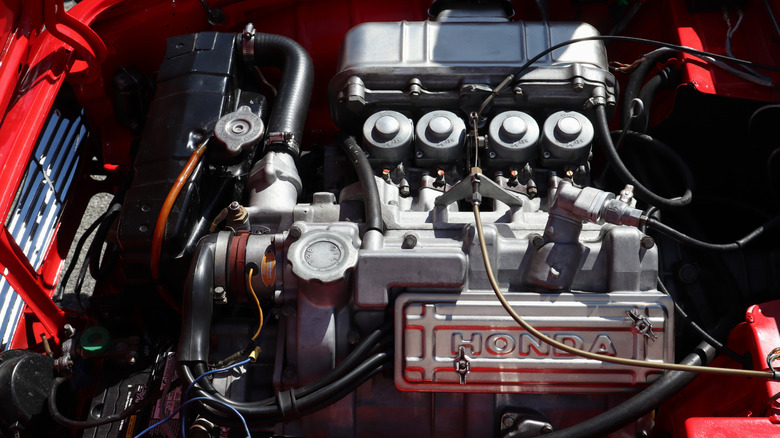

How Honda's S600 Sports Car Reached 9,500 RPM With Nearly Zero Oil Pressure

If you're lucky enough to get behind the wheel of the diminutive 1964-1966 Honda S600 sports car, as Jason Cammisa did for his Hagerty Revelations show, you'll notice there's no oil pressure light or gauge. This is because there basically isn't any pressure to measure. And yet, the tachometer shows a redline of 9,500 rpm, the highest redline of any production car before or since. Just listen:

Well, the key to that dental-drill spinning speed is largely due to Honda's use of roller bearings for the crankshaft. Normally, engine crankshafts spin on a thin film of oil between the crank's journals and plain hydrodynamic (or fluid) bearings. In Chevrolet and GMC pickup trucks with the 6.2-liter L87 V8, that film of oil was, until recently, thinner than the plot of a modern-day Marvel movie. But GM did start suggesting the use of heavier, thicker oils to help prevent further engine failures.

Anyway, most engines pass oil through the crank's main journals to small holes between the journal and the main bearings. Since these surfaces are ridiculously close to each other, there's measurable pressure as the oil gets forced through. This pressure is constant as long as the parts are within proper tolerance, but will drop as parts get worn out and tolerances decrease.

By tossing out plain solid metal bearings and swapping in roller bearings, oil pressure becomes incidental. Now, oil still gets splashed onto the bearings to make sure the rollers spin freely and maintain teeny-weeny hydrodynamic films between the roller surfaces, but oil doesn't need to feed through the crank journals. There may be some nominal oil pressure because an oil pump still helps circulate oil to lubricate moving parts, but nothing like the 25-30 psi in normal engines.

Roller bearing cranks are an exercise in complexity

Given that the Honda S600 revved so freely with so little friction, it might seem prudent to go ahead and make all engines with roller bearing crankshafts, right? In 2009, bearing manufacturer Timken grabbed a 3.5-liter V6 from a Toyota Avalon and converted its crank and cam trains over to roller bearings, and found that friction reduction was as high as 10%.

Even the thinnest modern oils can't keep up. As per a 1999 SAE paper from Honda, experiments showed 0W-20 oil usage improved fuel economy by 1.5%. But in Timken's paper, the company mentioned working directly with the EPA to determine the friction reduction impact with roller bearings and came up with a fuel economy improvement estimate of 5%. The thing is, as awesome as roller bearings are at kicking friction to the curb, they can present more problems than they solve, which is why auto manufacturers have abandoned them. Some motorcycles, such as Harley Davidsons, still use them, but it's rare.

Crankshafts, whether cast, forged, or billet, are almost always one solid chunk of zig-zagging metal. Roller bearings, unlike plain bearings, are solid circles that aren't meant to be split in half and pieced together around a crank or rod journal. Imagine trying to slip a roller bearing past counterweights and you'll understand the problem. So, in order to make a roller bearing crank, it has to be precision assembled piece by piece. Even worse, individual rollers can get stuck when the oil is cold. Over time, this develops a flat spot on the roller, which prevents it from rolling — its only job.

The siren call of reduced friction is hard to ignore

It somehow gets worse. Roller bearings can only be pushed so hard before they hit their fatigue limits. The Mercedes 300SLR's M196 S engine used roller bearings, but the German manufacturer limited its redline to reduce this fatigue during 24-hour races. In Formula One, cars used roller cranks off and on up to the V10 years before giving up the chase. Not only was the performance gain negligible, but the manufacturing was complex and the bearings ate up too much space. In 1996, the FIA banned the ceramic bearings most commonly used for the roller cranks, and everyone was happy to go back to regular crankshafts, anyway.

Bugatti (the first one, not the Romano Artioli or Volkswagen one) used roller bearing cranks, making assembly an arduous task, particularly for the company's straight-eights. Although Bugatti's engines became some of the most famous straight-eight engines ever made, the configuration is rare today. Advanced as they were, Bugatti's roller cranks were still highly temperamental and only lasted about 5,000 miles before needing to be swapped out. Porsche also experimented with roller-bearing crankshafts. The 356 and 550 Spyder used the Hirth roller crank, which became famous for being as robust as dried leaves.

The high-revving Honda S600 was a marvel, with its 57-hp oversquare 606 cc double overhead cam, aluminum block, hemi-headed, roller crank inline-four that propelled only 1,576 pounds of miniature convertible. Though Honda also used roller cranks in the prior S500 and subsequent S800 sports cars, as well as the two-cylinder N360/N600 sedans and plenty of motorcycles, the company eventually stopped trying to engineer around the design's shortcomings. While roller bearings featured in Honda's 1968 RA301E Formula One V12, plain bearings arrived in the subsequent RA302 V8. Honda also switched to plain bearings for its 1969 CB750 motorcycle and never looked back.