What Made The Chevy Powerglide Transmission So Special?

The Powerglide transmission used in Chevrolets and some other General Motors automobiles was introduced in 1950. While it wasn't the first automatic transmission, its simple design made it an affordable option for a wider range of car buyers.

First-generation Powerglide transmissions, produced until 1962, involved cast-iron housings joined with bolts and gasketed joints. Overall it was heavy, had a potential for leaking fluids, and its two-speed operation earned it the nickname "slip-and-slide Powerglide." While it had two forward gears, until 1953 it launched from a standstill in top gear, deriving its mechanical advantage from the torque converter and only slipping into low gear to negotiate steep grades.

It was the Powerglide's second generation, in 1962, that made it so special — a nearly indestructible transmission. Until it was discontinued in 1973, replaced by the Turbo-Hydramatic automatic, the updated Powerglide featured an aluminum case that contributed to an overall weight 100 pounds lighter than the original. Its robust construction and simple two-speed operation earned it a reputation for durability among drag racers, and with available aftermarket parts the entire transmission is rebuildable and stronger than ever.

Two-speed Powerglide gear ratios

Today's automakers have gone all in on automatic transmissions with increasingly higher numbers of gears. One main difference between the two-speed Powerglide and the 10-speed transmissions common today is the wide ratio versus close gear ratio variance between shifts.

Two-speed Powerglide automatic transmissions don't have an overdrive gear. Instead, the highest gear ratio, second gear, is 1-to-1 (1:1). While thinking of ratios might recall the pain many of us experienced in algebra class, the 1:1 ratio simply means the transmission's output shaft turns the car's driveshaft one full revolution for each revolution turned by the transmission's input shaft.

Powerglides intended for use behind six-cylinder engines of the day were equipped with a 1.82:1 first-gear ratio, while eight-cylinder versions had a first-gear ratio of 1.76:1. The lower gear ratio of the Powerglide's first gear having a larger initial number is counterintuitive. It means that the input shaft must turn more to complete a revolution of the output shaft: 1.82 or 1.76 revolutions, to be exact. For comparison, the first-gear ratio of GM's 10L80E automatic found in some last-gen Camaros is 4.70:1, with its 1.80:1 fourth gear being the closest approximation of the Powerglide's low gear.

How is a two-speed automatic better than a 10-speed?

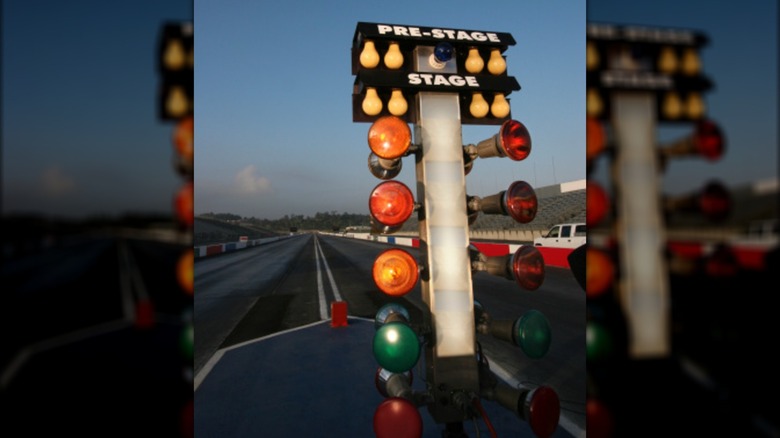

Shifting problems are among the biggest complaints about 10-speed automatic transmissions. One factor at the root of 10-speed transmission issues is the complexity of control modules and internal components. The simple operating parameters of the two-speed Powerglide are its biggest strength. That's what drag-racing teams rely on when building a car. Upgraded components available through aftermarket suppliers have erased any of the original Powerglide's shortcomings.

The question is how an antiquated two-speed transmission design can out-perform a modern 10-speed if both are operating at peak form. The answer lies in power delivery and consistency. Modern 10-speed cars use traction control or launch control to prevent wheel spin under acceleration. Neither system actually provides more grip to the tires. Instead, they both work by reducing engine power or, in some cases, employing the braking system to prevent wheel spin. And as everyone knows, brakes only slow you down.

The Powerglide's lightweight rotating assembly and higher initial gear ratio, coupled with the low rear-axle ratio often found in drag cars, works to provide consistent, usable power to the rear tires off the line. In addition, with its two speeds, the Powerglide only has to shift one time during each quarter-mile or eighth-mile pass. For a drag car, especially a bracket racer where consistency is key, fewer shifts represent fewer opportunities for mistakes that could upset the car and cause traction loss, resultin in longer elapsed times.