No One Can Seem To Agree On How To Measure Displacement Of A Rotary Engine, Here's Why

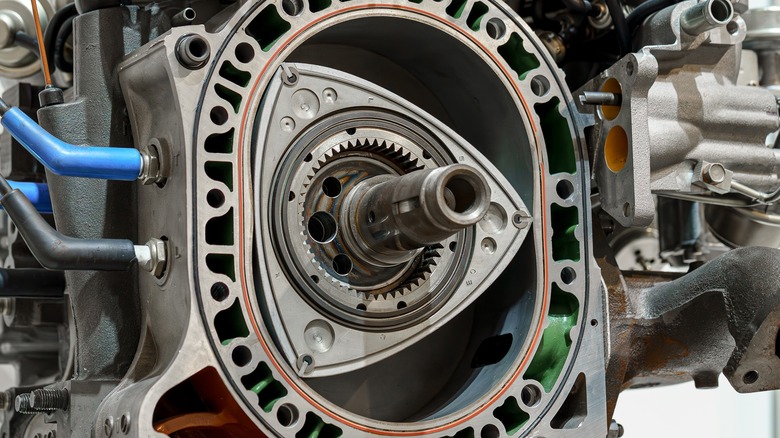

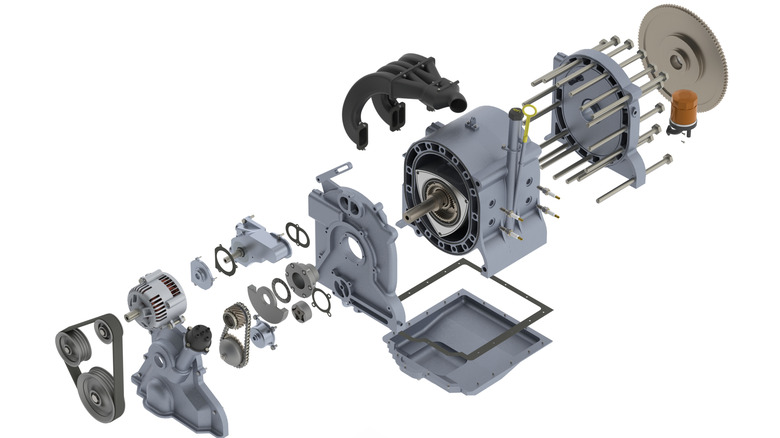

Language is an imperfect medium, but it's what we've got, so let's go with it. Determining the swept volume of inventor Felix Wankel's rotary engine can generate more arguments than claiming what a GT car is supposed to be these days, and that largely has to with how we use the word "displacement." Rotary engines are weird because instead of neat, clean, easily-measurable cylinders, we get this alien three-lobed tortilla chip thing that rotates in an odd figure-eight pattern around an eccentric shaft. The shaft is not called "eccentric" because it likes putting ketchup on ice cream, but because it's offset from the center of rotation.

Figuring out how much space is available for air inside the chamber created by the engine's bulbous triangle should be a relatively simple bit of math, right? After all, that's what we usually mean by "displacement." Let's calculate it using the formula given in Mazda's "Rotary Engine" book written by Kenichi Yamamoto, aka the father of the Mazda rotary engine. That formula is 3√3eRb, or three times the square root of three times "e" times "R" times "b."

Here's what those letters mean: Distance of rotor center to tip (R); eccentricity (e), or the offset between the center of the lobe inside the rotor and center of the crankshaft; and the width of the rotor housing (b). In a Mazda 13B engine, R equals 105 mm, e equals 15 mm, and b equals 80 mm, giving us a volume of 654.7 cubic centimeters per rotor and a total of 1.3 liters (1,309 cc) between the two rotors.

So, we're done here, right? Rotary displacement solved!

Not quite. The problem is, this formula only calculates the volume for a single chamber, while each rotor effectively creates three.

Four-stroke, two-stroke, or something in between?

In a Wankel engine, each surface of the rotor is in a different part of the combustion cycle at any given time. Rotaries act like four-strokes, going through suck, squeeze, bang, blow as sequential steps for each rotor face. And yet rotaries act similarly to two-strokes because there's one power cycle for each 360-degree rotation of the crankshaft.

Why does the formula not calculate volume for all three chambers at once, then? It might be that Mazda only wants to measure chambers actively in their combustion cycles (the volume formula in "Rotary Engine" is for the "working chamber"), but we count cylinder volume in piston engines regardless of which stroke they're working on. This is the point made in Hemmings in a quote from G. Fred Leydorf, an advanced-engine engineer for American Motors, which once considered making a rotary engine for its Ramblers. In 1973, Leydorf said, "With the Wankel ... all three chambers of each rotor complete the four-stroke cycle — so they have to be counted in its displacement."

That Hemmings article also mentions NSU, the German company that was one of the early adopters of Felix Wankel's revolutionary rotary engine, and why the company used the single-rotor displacement figure. Max Bentele, an engineer for Curtiss-Wright, visited NSU in 1958 and told the company that it could avoid being overly taxed for its engine sizes in Europe if it only reported the single-chamber displacement, a practice Mazda adopted and continued.

So we can count rotary displacement with a single chamber per rotor — commonly referred to as "geometric displacement" — or we can count all chambers, called "thermodynamic displacement." And that's it, that's how we can determine rotary displacement, right? Right?

There's another way to determine displacement

There's a third option. Of course there's a third option. The displacement of a Mazda 13B is either 1.3 liters (1,309 cc) with the geometric method or 3.9 liters (3,927 cc) with the thermodynamic method, but you'll hear some people refer to the engine's displacement as 2.6 liters (2,618 cc). This is using "equivalent displacement." Since the 1.3-liter rotary makes a power stroke with every 360-degee rotation while a 2.6-liter four-stroke piston engine makes power every 720 degrees, people argue that the 1.3-liter single-chamber displacement should be doubled because it's making twice the number of power strokes. It also effectively calculates displacement for two chambers.

The problem here is that we don't double two-stroke engine displacements, so why do it for rotaries? It's because the "equivalent displacement" method is useful for racing classification to make sure rotary-powered cars don't slip into small-engine categories and sweep the podium. It's a pragmatic approach, like how Formula 1 used to have different rules for naturally aspirated and forced-induction engine displacements to keep the playing field even. Rotary engines may have some potentially crippling downsides, such as oil consumption, poor fuel economy, and apex seals that wear quickly, but power-to-displacement isn't one of them.

But if we want to take "equivalent displacement" and "thermodynamic displacement" to their logical conclusions, why not double the three-chamber displacement like some people do with the single-chamber displacement? Can we honestly say that the Mazda 13B isn't a 7.9-liter (7,854 cc) engine? We'll call it "hyperbolic displacement."