Why Did Tailfins Have To Disappear?

On October 16th 1977, The New York Times published an article titled, "As Useful as Rust, Tail Fins Were an Outrageous Rage." In it, author Jerry Flint writes, "Yes, fins were the most glorious expression of automotive irreverence ever. They not only did absolutely nothing; they didn't even seem to fit on wheeled rovers of the land. But logic didn't matter, and any car without fins was hopelessly old fashioned." While the piece is generally favorable toward tailfins, and even exhibits a wistful nostalgia for a more optimistic and colorful automotive era, writing that tailfins did "absolutely nothing" stings. Tailfins did have a purpose: To stir the human soul and remind us that cars do not have to be mere conveyances, but that they can also be works of art.

Tailfins entered the automotive vernacular thanks to the 1948 Cadillac's taillight nubbins. General Motors' design chief, Harley Earl, had taken his stylists on a field trip to Selfridge Field nine years earlier to get some inspiration from the military's Lockheed P-38 Lightning. They were in awe, particularly Franklin Quick Hershey. The P-38's memorable vertical stabilizers percolated in Hershey's head until they spilled out into the design for the '48 Caddy's flowing, yet tentative fins.

Fast forward to 1959, and the Cadillac lineup contained the tallest, most extravagant fins the brand (or any brand) would ever receive. They were the culmination of the "bigger is better" tailfin ethos, and from here, tailfins atrophied into the aether. Admittedly, tailfins became one of the more outward symptoms of the industry's hubris, and by the early 1960s, the public had grown tired of tailfins dominating design language. It also didn't help that folks such as Ralph Nader were pointing out that the sharper tailfins were pointing into pedestrians, too.

The space age and one-upsmanship

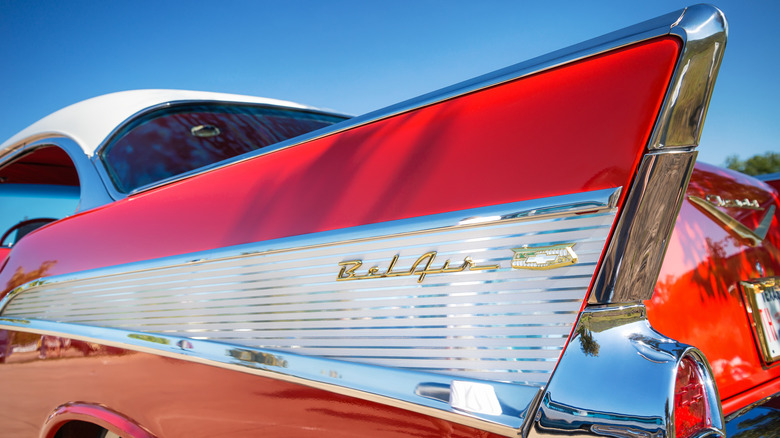

The height of the tailfin era just happened to coincide with the beginning of the space race. In 1957, the world experienced two pivotal events. The first event was the launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. The second event was the debut of the very cars many of us think of when the word "tailfin" is uttered: The 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air and 210. As aircraft and rocket technology advanced, so did the fascination with anything space-related. Automotive designers were more than happy to copy aerospace imagery, and what was more aero-spacey than fins?

GM wasn't alone in tailfin adoption; there were epic fins throughout several manufacturers' lineups. The 1957 Chrysler 300 had lovely swept rocket-ish fins that seemed to grow naturally from the car's beltline, and the fins looked as if they supplemented the 392 Hemi's thrust. Christine-era Plymouth Fury fins were similarly aeronautic, but kinked up well behind the roofline in a manner closer to that of a Cadillac Fleetwood. Ford's tailfins were more understated, but still quite present, and in particular gave Thunderbirds a sense of speed, whether moving or not. Non-American manufacturers such as Ferrari and Volvo adopted tailfins, too, and even Mercedes, whose "Fintail" era is a wonderful example of subtle fin incorporation (fin-coroporation?).

Around ten years after they first appeared, tailfins were seen as a vestige of a self-indulgent, restraint-free, styling arms race between manufacturers. John F. Kennedy famously said in 1960, "We have the most gadgets and the most gimmicks in history, the biggest TVs and tailfins. But we also have the worst slums, the most crowded schools, and the greatest erosion of our national resources and our national will." Ouch. Tailfins had grown too large, and after flying close to the sun, they melted.

Hazardous at any velocity

Capping off the derision of tailfins as a sign of excess were safety concerns raised by Ralph Nader in his 1965 book "Unsafe at Any Speed." He compared fins to a stegosaurus tail, and referenced several graphic accidents and where tailfins were involved. To be fair to Nader, he had valid criticisms, like the recommendation that seatbelts needed to become mandatory equipment (which happened in 1968). Considering other embarrassments like the industry's insistence on intellect-diminishing leaded gas and the use of whale oil in transmission fluid, there's a pretty strong case to be made that manufacturers' didn't have much foresight at the time.

Seatbelts, airbags, modern collision detection systems, and automatic cruise control are Godsends for safety, and have likely done far more good than eliminating tailfins, but if you've ever destroyed a shin on a protruding trailer hitch, you know there are still automotive dangers lurking today. And few of them are as good-looking as a classic tailfin.

Opinions incoming: Car enthusiasts often eschew such trivialities as reliability or comfort, as we expect cars to delight us through acceleration, handling, exhaust note, or appearance. If a car is also safe, reliable, or comfortable, well, that's a bonus. But tailfins seemed to have pushed the limits. They grew too large for the general public to continue appreciating their beauty, but we all know better, right? More flare is just plain better. Compare the '57 Chevy Bel Air's two-tone fins with the plain-trimmed 150 fins and say, with a straight face, that the 150s look better.