Why Inline-5 Engines Don't Play Well With Carburetors

Pop open the hood on a Ferrari 250 GTO (if you happen to own one or are part of a team that restores these $70-million cars when they go up in flames), and you'll see a 300-horsepower V12 with six twin-throat Weber carburetors. Each carb has two barrels (or throats), meaning each cylinder gets its own and doesn't have to share. This is an exotic racing engine from the 1960s, so this elaborate fuel-feeding setup is understandable. But if you wanted to make a five-cylinder engine run with carburetion in any pleasant, fuel-efficient, powerful, smooth, or low-emission manner, this barrel-per-cylinder setup would be your only workable option.

We've written about the pros and cons of five-cylinder engines before, but only touched briefly on the carburetion issue. The five-cylinder engine hates carburetors. Hates them like Jeremy Clarkson hates Porsche 911s. This is an issue worth exploring because the five-banger suffered decades of development inactivity largely due to its incompatibility with what is, in essence, a glorified perfume atomizer. Seriously, Wilhelm Maybach's patented float-feed carburetor design from 1893 was inspired specifically by his wife's perfume atomizer. It's a (relatively) simple device that wreaks havoc with fives, and it largely comes down to two issues: the firing order and which cylinder gets fuel first.

For the most part, five-cylinder engines are also inline engines, which are the ones mainly discussed here. There are layout outliers, like Volkswagen's VR5, Honda's MotoGP bike V5, and airplane radial engines. Radials are drastically different designs with their own quirks and firing orders. In a radial-five, the firing order is 1-3-5-2-4, which is the same star pattern you'd use to put lugnuts on a five-lug wheel. There is no central cylinder to hog fuel. Same with even-numbered inline and V engines.

The middle cylinder wants it all, and the others won't share, either

Imagine what a carbureted five-cylinder engine's intake manifold must look like. Carbs are usually located in the center because fuel must be distributed as equally as possible. Outboard cylinders will get a reasonably equal amount of air and fuel, but the one in the middle will drink from the proverbial fire hose. Add another carburetor, and you run into the problem of tuning them to each feed 2.5 cylinders. The problem doesn't disappear until you get to five carbs or a single five-barreled carb.

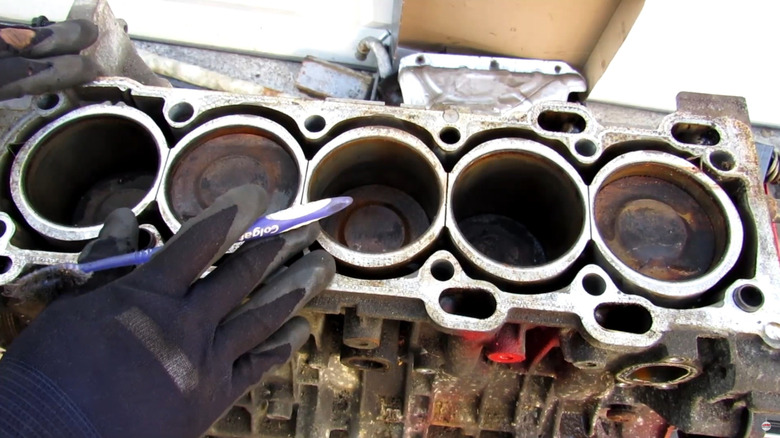

The central-cylinder feeding issue isn't a big deal with three-cylinder engines, although threes have plenty of pros and cons themselves, because threes don't have a firing order that fights carb tuning. Yes, the five-cylinder's firing order is the real hair puller. Here's a Volvo T5 without its cylinder head. Notice the order in which cylinders appear at top dead center:

That's a firing order of 1-2-4-5-3. In fives, you get a power stroke every 144 degrees of crank rotation, and that order minimizes rocking couples that cause the engine to want to see-saw around the middle of the engine. Unfortunately, there are two times where successive cylinders fire right after each other. This means that as one piston is in the middle of its intake stroke, the one next to it is starting to suck fuel and air in, too, meaning they're fighting each other just to breathe. Even with a Chevy Colorado inline-five's firing order of 1-3-5-4-2, this would still happen.

This is why inline-sixes can be carbureted despite having long runners. With a firing order of 1-5-3-6-2-4, there are never successive cylinders battling for oxygen and gasoline. The same goes for an inline-8 with a firing order of 1-4-7-3-8-5-2-6.

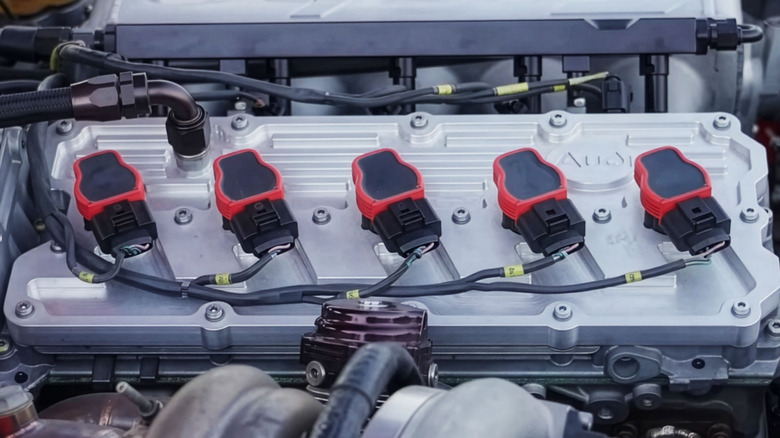

Well, Audi managed to carburate a five-cylinder engine

Having talked about how five-cylinder engines relate to carburetors the same way vampires relate to sunlight, let's discuss Audi's 1978 carbureted inline-five that made 115 horsepower at 5,400 rpm. Somehow this affront to engineering was used in the B2 Audi 80 CD, C2 and (briefly) C3 Audi 100s, and the Audi Coupé GT 5S. Here's an Audi 80 with a carbureted five that sounds pretty darn good:

Looking through the manual for the C3 Audi 100 with the carbureted five-cylinder, which was using a Keihin carb at that point (it seems Zeniths were also used from 1979 to 1982). It doesn't appear that there are special tuning instructions related to the five, so what's the deal?

A clue comes from a forum post in the Fiat Coupe Club, of all places. Poster Barmybob says he worked on many a carbed Audi five, and Audi killed it for emissions reasons. This would make sense because, as you can see in the picture above, the manifold places the carb in the center with the shortest runner going to the center cylinder. So, different cylinders would run rich or lean in a neverending cycle, causing power fluctuations, rough idling, and poor emissions. Couple that with fuel injection becoming the norm in the '80s, and it's not hard to see why Audi abandoned carbs. Heck, Audi's barely holding onto 5-cylinder engines, period.

Fuel injection can distribute fuel more equally to each cylinder, making tuning far simpler. And well, the fuel-injected version of Audi's late-1970s/early-1980s five made 136 hp at 5,700 rpm, 21 hp more than the atomizer-fed motor. So it seems you actually can carburate fives — as long as you don't mind all the reasons it's a bad idea.