What's The Difference Between A Single- And A Dual-Clutch Transmission?

Raise your hand if you answered that the difference between a single and dual-clutch transmission is one clutch. Excellent. We're halfway home.

Single-clutch and dual-clutch transmissions differ in how they are designed to select gears, but they actually share fundamentals. Power reaches the drive wheels by transferring engine torque through a rotating, gear-lined input shaft — coupled to the engine flywheel via the clutch — that meshes with gears on a corresponding output shaft. The idea is to select gears that work in harmony with the engine as revs increase and decrease, whether there's one clutch or two.

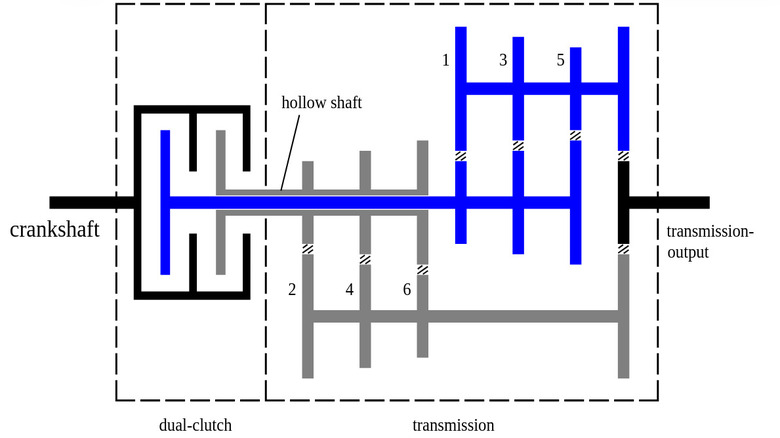

Their roads diverge from here. Single-clutch transmissions, often called SCTs, use one shaft for input gears and another for output gears. Only a single gear can be selected and engaged at a time, either manually, as with a clutch pedal and shifter, or electronically. Dual-clutch transmissions — often DCTs for short — trade a clutch pedal for an extra clutch, one for odd gears, and one for even gears, and separate those odd and even gears on two shafts. The clutches operate electronically. That means while you're tooling around in third gear through one clutch, the other is pre-selecting the next gear — say, second or fourth — to be engaged almost instantly. Manual input is optional.

Clutches 101: How a clutch works

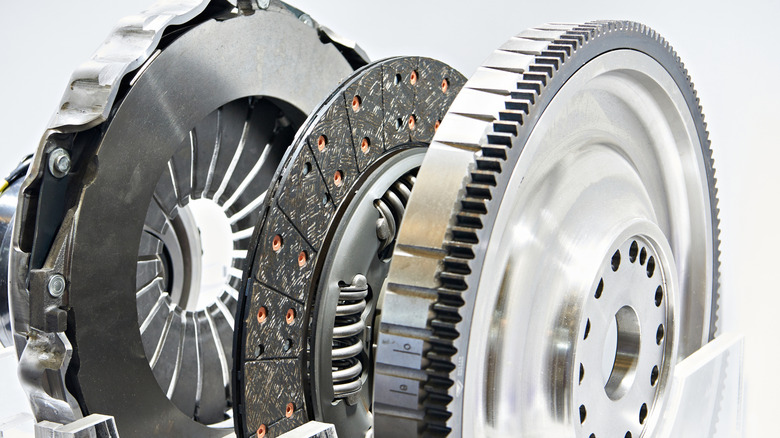

Clutches do the same thing in single- and dual-clutch designs: they act as power brokers between engine and transmission. When an engine revs, it sends power through the crankshaft to a flywheel, which harnesses and makes that power smoothly transferable to the clutch, which connects to the transmission input shaft.

A clutch is a set of three components that sandwich together: a clutch disc, which mounts on the transmission input shaft splines like a record on a turntable hub, and grips the face of the flywheel; a pressure plate that holds the clutch disc to the flywheel face; and a diaphragm spring, which helps the pressure plate keep the clutch disc in contact with the flywheel.

In a manually operated single-clutch transmission car, an arm, or clutch fork, pivots behind the pressure plate like a little crowbar to relieve tension on the diaphragm spring, uncouple clutch from flywheel, and engine from transmission. Depressing the clutch pedal moves that fork.

The unholy crunching sound of a poorly executed manual gear shift is the result of ill-timed clutch-flywheel engagement under throttle — or trying to shift without depressing the clutch — forcing gears to mingle at different speeds. Dual-clutch transmissions avoid that noise by having electronics do the tap dance.

Single-clutch simplicity

Single-clutch transmission roots date at least to 1891, with French inventor Louis-René Panhard's sliding gear system. Borg & Beck's George Borg introduced notable clutch design refinements in 1910 that reflect modern designs, despite not knowing how to drive. Materials have improved, yet the operation of a manual SCT remains the same today.

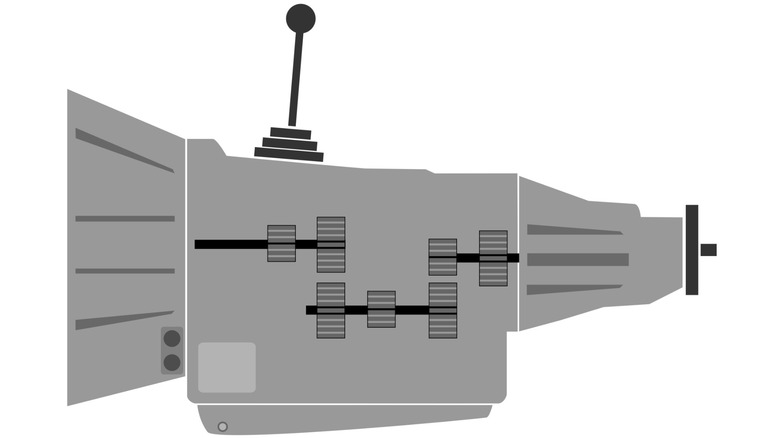

Inside a single-clutch car transmission, the gear sets are stacked sequentially on the input and output shafts — first, second, third, and so on. You're always moving up and down this line, for as long as it takes to move from gear to gear as you accelerate and decelerate.

Input gears are fixed in place along the input shaft, so the whole assembly spins when the clutch is engaged. The output gears rotate freely on the output shaft, and don't transfer power until they are locked into place by moving the gear shift selector through its pattern. (Selecting reverse cuts into the input/output party with a nifty gear set on its own shaft, designed to spin the output shaft in the opposite direction.)

Depressing a clutch pedal effectively cuts power from the transmission on that single row of gears, so you can rifle through changes manually — which is how single-clutch transmissions have largely soldiered on — but there are electronic examples on the SCT family tree. The sequential unit in the 2002 E46 BMW M3 SMG boldly cut out the clutch pedal in favor of a computer-controlled electro-hydraulic system. It was innovative, but some readers felt it ruined a great car.

Dual-clutch dynamics

Dual-clutch transmissions hit showrooms with the 2003 Volkswagen Golf R32, but their DNA dates back to Adolphe Kegresse in 1930s France. Porsche's modern PDK system sprang from the company's 1960s dual-clutch prototype that was refined in the 1980s. Back then, Porsche took its new toy racing, winning with it at Monza in 1986, while Audi savored dual-clutch victory in the 1985 Semperit-Rallye. In addition to those Volkswagen Group marques, BMW, Chevrolet, Hyundai, and Nissan have also, in partnership with companies like Borg Warner, Getrag, Tremec and ZF, brought dual-clutch units to market.

Driving a dual-clutch is like having two transmissions at your precise command to alternate between by flicking a toggle switch. Power is almost constantly being transferred to the wheels with efficiency. One clutch controls your odd-numbered one-three-five gear shaft, while the other clutch controls even-numbered two-four-six gears on another — and these shafts can rotate independently. So beyond simply lining up the next gear for input, the other clutch already has the next gear spinning, and can electronically kick it in within milliseconds by engaging one clutch, and cutting off the other one.

It's possible to pulse down from sixth directly to third gear onto an exit ramp — without hellish grinding — because of how dual-clutches can jump between those respective gear shafts. One clutch with one gear set on one output shaft can't pull that trick, even with digital oversight.

Dual-clutches let you choose your own adventure in manual mode, often with paddles on the steering wheel or a bump of selector stick on the console. Or all of this can be done automatically for you — but dual-clutches and automatics are different beasts.

Automatic versus dual-clutch designs

Despite having computer brains with an automatic mode, dual-clutch transmissions are not automatics. How automatics change gears is a whole other story, starring torque converters and planetary gearsets. General Motors launched the first fully automatic transmission on 1940 Oldsmobiles as an appealing, convenient alternative to DIY gear selection. While automatics continue to improve, and are the mainstream choice today, single-clutch manuals remain popular in enthusiast circles.

The dual-clutch transmission, with its single-clutch-like heart and automatic brain, aims to offer the best of both worlds: smooth city comfort for the road, with track-day chops at the ready. The swift, on/off nature of dual-clutch shift engagement can feel abrupt or jarring at low speeds inching up at stoplights, but modern dual-clutches feature different driving modes that help overcome this sensation. Even for the most ardent clutch pedal disciples — not to mention those of us who have a balky left knee — rapidly flicking through dual-clutch gears without having to use a pedal can deliver its own special, liberating thrill.

Shopping single- and dual-clutch cars

Since BMW ditched its electronically-controlled SMG offerings in 2010, you'll have to hit the used market to find a single-clutch transmission that isn't a manual. Shopping for a car with a manual in 2025 offers some great choices, like the Acura Integra Type S, Honda Civic Si, BMW M2, or the Ford Bronco and Jeep Wrangler if you're looking for something rugged. For some people, manual shifting offers a direct connection and joy that can't be replaced, even if clutch work can be a total pain to live with in city driving and traffic.

Porsche and Audi offer double-clutch transmissions in their lineup, as does Hyundai, and the Volkswagen Golf GTI rocks one as well. While there are whispers of a manual C8 Corvette, that car is currently only available with a DCT. As you can probably tell from that list, double-clutches skew towards the performance side of the market.

Car companies may love DCTs, but they also have some trade-offs for anyone seeking the fully automatic experience. Ridiculously fast gear changes, and the ability to shift with both hands on the wheel, make double-clutch transmissions well-suited for enthusiasts who like to control the action, but might also appreciate being able to kick things into auto from time to time.