Police Used Flock Cameras To Track One Driver Over 500 Times. Now They're Being Sued

Humans have excellent gaze detection. We know instinctively when another person is staring our way. But unless a camera is particularly conspicuous, like the creepy "human-eyeball" webcam created by Marc Teyssier at Germany's Saarland University (per Science Codex), it's nearly impossible to know when we're under the tearless retina of the electric eye. Oh, we expect cameras to snap a pic of us when we run red lights or speed through toll booths. But should cameras be capturing us all the time, regardless of our actions?

That's not a rhetorical question. A retired veteran named Lee Schmidt wanted to know how often Norfolk, Virginia's 176 Flock Safety automated license-plate-reader cameras were tracking him. The answer, according to a U.S. District Court lawsut filed in September, was more than four times a day, or 526 times from mid-February to early July. No, there's no warrant out for Schmidt's arrest, nor is there a warrant for Schmidt's co-plaintiff, Crystal Arrington, whom the system tagged 849 times in roughly the same period.

You might think this sounds like it violates the Fourth Amendment, which protects American citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures without probable cause. Well, so does the American Civil Liberties Union. Norfolk, Virginia Judge Jamilah LeCruise also agrees, and in 2024 she ruled that plate-reader data obtained without a search warrant couldn't be used against a defendant in a robbery case. If rejecting such evidence sounds like it goes too far, especially in a robbery case, it's worth pointing out that the same year, license-plate-scanner data led to a Detroit woman's wrongful arrest.

What the actual Flock?

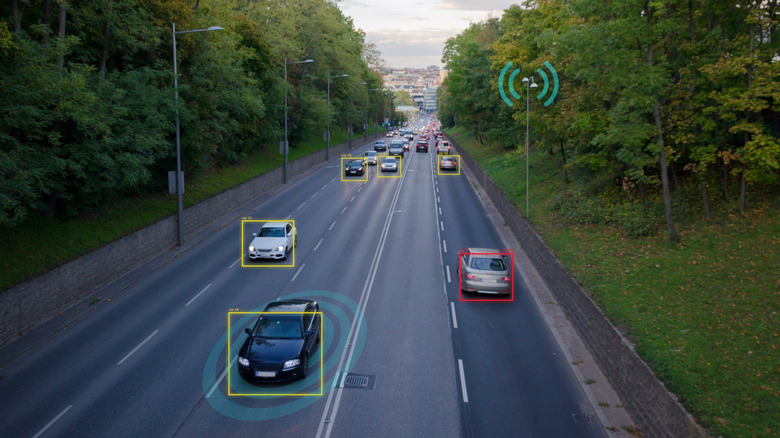

If you're not familiar, Flock Safety is a private company that maintains databases of data taken from plate-reader cameras. Flock Safety writes on its website, "License plate recognition (LPR) cameras can be placed almost anywhere to capture detailed data about license plates and vehicles used to commit crimes, enabling quick and efficient action."

Yet a Flock Safety spokesperson told NBC News, "Fourth Amendment case law overwhelmingly shows that LPRs do not constitute a warrantless search because they take point-in-time photos of cars in public and cannot continuously track the movements of any individual." This sounds like a lovely little linguistic loophole: The cameras don't continuously track people's movements, they're stationary! But they "capture detailed data about license plates," which enables "quick and efficient action." That sounds a lot like tracking.

While the cameras are mostly affixed to telephone poles and streetlights, and take pictures of cars, not people, they also can be mounted on tow trucks and police vehicles. Once a plate is spotted, police can use GPS to pinpoint its location. They can also do something called "gridding," where a vehicle with a plate-reader camera just cruises around neighborhoods to gather intel.

And now, Flock Safety wants to team up with Nexar, a dashcam company, to transform dashcams into surveillance tools. If that makes you concerned, it's okay — Ring doorbell cameras have been sending data to hundreds of contracted law enforcement agencies since before the pandemic, so we should be used to it by now.

Who watches the watchmen?

In episode 143 of Hagerty's "The Carmudgeon Show," Jason Cammisa reported that Honda, Acura, Hyundai, and Kia sell consumer driving data to LexisNexis Risk Solutions, which then sells it to insurance companies. Don't worry, it can just lead to increased insurance premiums. LexisNexis collects plate-reader data, too, and the company's website states, "LPR technology continues to transform investigations by expanding the reach of law enforcement."

Even if monitoring driving data spotted risky drivers and plate readers reduced crime, they're systems that seem easy to abuse. A police chief in Kansas used Flock Safety cameras to track his ex-girlfriend and her boyfriend, even following them out of town in a police vehicle. Of course, this was stupendously illegal and the chief resigned. But what's unnerving is that his actions weren't uncovered or even suspected by anyone. He was being investigated for entirely unrelated misconduct, and blurted out that he was tracking his ex. A lack of oversight seems to be an issue here.

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin signed a law in May limiting the circumstances where license plate data can be accessed, and it goes into effect in January 2026. Under the law, authorities will only be able to obtain data during active criminal investigations, missing and endangered persons cases, and in cases where a car or license plate has been stolen.

You may notice that this means the cameras will still be recording. All this law does is tell law enforcement when they can access the footage. The Schmidt-Arrington case is about being recorded at all, and as the Kansas police chief case shows, that's the crux of the issue. Taking the pictures but restricting access for the moment is like requiring everyone to get a mug shot in case they commit a crime someday.