America's Most Powerful Locomotive Was So Extreme, Cities Had To Ban It

It was the 1950s, a transitional postwar era when road transportation was still picking up pace, and railways did the heavy lifting. Steam engines were on the way out as diesel locomotives gained a foothold in railway logistics.

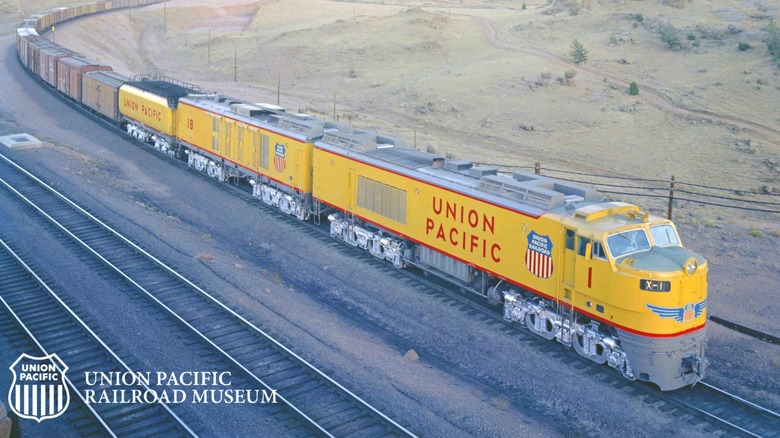

However, Union Pacific, a U.S. railway conglomerate, saw things differently. Obsessed with the "Gross Ton-Miles per Train-Hour" formula that calculated transport efficiency, it wanted a torque monster that would replace multiple locomotives needed to pull a long convoy of coal cars up a mountain without breaking a sweat. The answer was the Gas Turbine-Electric Locomotive (GTEL), which seemed to bend the laws of physics with its cost efficiency and sheer power.

The need for such a monster was simple: power density. Diesel-electric locomotives performed better than steam engines, but were bulky, and put out just 1,500 horsepower. One of the biggest challenges for Union Pacific was pulling heavy loads through terrains like the Wasatch Grade, a 65-mile-long climb with a 1.14% incline through Utah's Wasatch Mountains. It was one of the reasons Union Pacific developed the 4-8-8-4 "Big Boy" steam locomotive. Even on flatter routes, it wasn't uncommon to see a 200-car-long convoy being moved by up to five diesel locomotives.

This need for efficiency led Union Pacific to develop the GTEL. The railroad wanted more power per axle, and the GTEL delivered four times the power of a diesel-electric locomotive — enough to transport a 5,000-ton rail convoy across the Wasatch Mountains without breaking a sweat. But it came with a downside: It was so loud, powerful, and hot, some cities wouldn't let it pass through.

The mechanics behind the monster

The premise behind the GTEL was simple, unlike that of the Napier Deltic, one of the strangest locomotive engines ever built. Think of a gas turbine mounted sideways, powering traction motors. Its workings were similar to a diesel-electric locomotive's, but instead of a diesel engine, the massive turbine was attached to a generator, creating electricity to power the traction motors. But it was way more complex than that. A gas turbine is like a fiery furnace, so it has to be built to be able to withstand large thermal stresses.

Then came the running sequence. The GTEL was a two-part monster, with the "A" unit housing an auxiliary diesel engine, while the massive "B" unit carried the turbine and generator. To start a GTEL, the diesel auxiliary was fired up, which cranked the turbine until it reached self-sustaining speeds. Fuel and compressed air were used to set the engine in motion. This mixture was ignited and the resultant hot gases expanded, moving the turbine blades and driveshaft. This driveshaft powered a generator which, in turn, sent power to eight electric traction motors.

Third-generation GTELs could push out over 10,000 horsepower, but were capped at 8,500 to keep the electrical generators from melting. To keep the turbine running, a specialized tender containing 24,000 gallons of fuel was hitched to the GTEL. Besides helping supply near-unlimited tractive power, this fuel also offered significantly cheaper operations (on paper). It wasn't diesel or gasoline.

Bunker C, a monster fuel

If you thought the GTEL was enigmatic, wait until you hear about Bunker C. It was the ultimate budget fuel in the 1950s, real bottom-of-the-barrel stuff, quite literally. Bunker C is a heavy residual fuel oil that's left over after refining petroleum. It's used as fuel in large marine engines, industrial boilers, and even in power plants for its high energy content and low cost. At room temperature, Bunker C has the consistency of molasses, and to make it usable, you have to heat it up. To make it viscous enough to flow through the fuel lines and injectors, the auxiliary diesel engine preheated the fuel inside the tender to 200 degrees Fahrenheit with the help of electric elements.

In the '50s, Bunker C was considered a waste byproduct of refineries and, therefore, was cheap. It was the most cost-effective way to move over 10,000 tons of freight at the time, provided the turbine was kept under full load. That's because the GTEL turbine was efficient at full throttle, but consumed nearly as much fuel while idling. While Bunker C was cheap, the amount consumed was staggering and could quickly empty the 24,000-gallon fuel tender.

The GTEL's low running costs were predicated on the easy availability of industrial waste fuel, a gamble that paid off handsomely until the oil industry found other ways to put Bunker C to use. Meanwhile, to keep the engine at peak efficiency, GTEL engine crews kept them running at full throttle all the time. And this posed a major problem.

Auditory warfare

The GTEL earned the nickname "Big Blow" due to its high-pitched jet engine sound. Unlike the rhythmic thrum of a steam engine or a diesel locomotive, at its operating speed, the GTEL assaulted your hearing with its constant, piercing wail. It was basically a jet engine strapped inside a railcar with the exhaust on the roof, through which gases exited at speeds of 150 miles per hour under full load, reaching temperatures of 850 degrees.

GTEL trains could be heard from a long distance, and chances were you'd not only hear it coming but feel it in your chest way before you actually laid eyes on it. The noise emanating from the turbines at operating speeds was so penetrating that the GTEL crew used the auxilary diesel engine to move the locomotive around in the train yard. This noise created a lot of issues for Union Pacific, especially when GTELs entered any town or city.

Banned in Southern California

Union Pacific faced no problems running GTELs through the wide-open expanses of states like Utah and Wyoming. The real trouble began when they tried to cross cities. In the 1960s, Union Pacific attempted to run the GTELs between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. This move turned out to be an unmitigated PR disaster. As the trains ran through Southern California suburbs, complaints started pouring in. Residents reported noise loud enough to be heard miles away from the railway tracks. The noise and vibrations were intense enough to break dishes and crack the plaster on the walls.

Another issue was the heat. As the trains passed under low-hanging railway bridges, the intense heat could melt the asphalt. Birds flying over the locomotive and through the black exhaust plume would be incinerated, earning the GTEL another nickname: "Bird Cooker". (Still, it wasn't as crazy as Daddy Long Legs, a wild high-rise train equipped with lifeboats.)

Under pressure from residents, most California cities banned GTELs, and Union Pacific was forced to limit their use to remote stretches between Council Bluffs, Iowa and Ogden, Utah. The California bans weren't the main reason for GTELs' downfall, though.

The end of a titan

By 1970, GTELs had ceased to exist. Like the Maglev trains that died in the U.S., the most powerful locomotive in America was no more. And this was mainly due to two factors.

The first was the very reason that had made the GTEL financially viable — Bunker C fuel. Bunker C was so cheap at first that despite GTELs' massive thirst, they were more cost-effective than a bunch of diesel engines. However, by the late 1960s, companies had started using Bunker C fuel to make plastics, and had learned it could be broken down to make lighter fuels. A fuel residue that had been easily available became rare, prices skyrocketed, and running the GTEL on Bunker C became prohibitively expensive.

The second issue was reliability. While running multiple smaller diesel engines, you can get away with one failing. With GTELs, the turbine failing meant the whole train was dead. GTEL turbine blades needed constant overhauls due to the corrosive nature of Bunker C fuel, and the engines needed a separate maintenance facility and service crew with the technical knowledge to maintain jet engines.

The rising fuel and maintenance costs led Union Pacific to pull the plug on GTELs by 1970. Of the 55 GTELs made for Union Pacific over two decades, only two survive today, parked at railway museums. The number 18 GTEL sits in the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois, and the number 26 GTEL is at the Utah State Railroad Museum in Ogden, Utah.