This 1909 Car Helped Customers Save Money With One Slight Catch

There are a lot of reasons Americans are sitting on $1.7 trillion in vehicle debt and a $1,000-per-month car loan is the new norm. However, historically speaking you may want to blame Charles H. Metz. After all, he's credited with the idea of the automotive installment plan that lets consumers buy a car with monthly payments. It was a huge deal because, at the time — 1909 — folks usually had to pay for cars with cash when they took delivery.

Needless to say, that was no simple task for the typical would-be car owner. The Model T had been introduced in 1908 as an inexpensive way to get folks on the road, but it still cost about $850 (around $30,000 in today's money). Sure, this was much cheaper than other cars of the time, which could set you back $2,000 to $3,000, yet the Model T still represented approximately five years of saving for the average family. Metz, on the other hand, had developed what he said was a $600 car that you could buy for just $350. Even better, you could pay over time in 14 installments of only $25 each.

Of course, the headline notes, there was a bit of a catch: Each $25 payment was for a box of parts (tools and instructions included), and you had to put the car together yourself. It would be another 10 years before GM brought automotive financing to the big time with the launch of the General Motors Acceptance Corporation.

Meet Charles H. Metz

Born in 1863 in Utica, New York, Metz became an avid bicycle fan (like our Amber DaSilva, who recently bought herself a proper bike). With his mechanical expertise, Metz was soon hired as a designer by a Massachusetts bike-making firm. The experience inspired him to start his own bicycle business in 1893, the Waltham Manufacturing Company, named for its location in Waltham, Massachusetts. From those roots, Metz eventually created the first American motorcycle brand, too.

Disagreements with the company's investors soon followed, though, and Metz was forced out — but he was back again in 1908 to try to save Waltham from the financial chaos it went through without him. The company had started building some pretty basic four-wheel vehicles in Metz's absence. And it was the huge inventory of unused parts that gave him the idea for the Metz Plan. Rather than put them together, he'd box them up and sell them as is.

This wasn't the first time an automaker had sold unassembled cars. Sears started selling its mail-order Motor Buggy at about the same time, and that required owners to get their hands dirty as well, attaching the wheels. The difference was that Sears still required payment up front, and you received one very large box containing all necessary parts. (In fact, the boxes were so big and heavy — weighing about 1,400 pounds — customers had to arrange to pick them up at local railroad depots.)

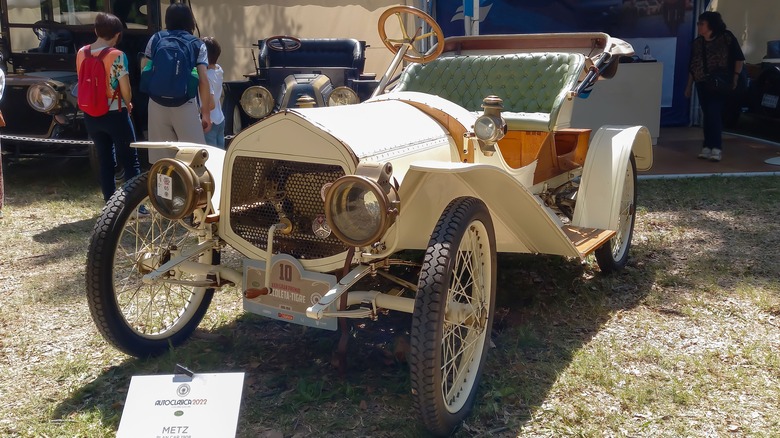

The Metz Plan Car

The original Metz Plan Car was a roadster with a relatively small 81-inch wheelbase with a standard track of 48 inches; for context, the wheelbase of the current Fiat 500e — a vehicle that proves why EVs make the best city cars — is some 10 inches longer in both dimensions. (Note: You could widen the Metz's track, to 56 inches, during assembly.)

Providing the car's movement was a two-cylinder engine capable of making 12 horsepower, and it relied on a friction drive, where power is transferred from engine to wheels using the friction between two pieces of metal in direct physical contact with each other. Modern automatic transmissions with torque converters rely on a fluid coupling, in which there's no metal-to-metal contact and the physics of the transmission fluid come into play to transfer power.

According to an anonymous owner, quoted in a 1910 Metz advertisement (via Classic Speedsters), one Metz Plan Car could take the place of "two driving horses ... at considerably less expense than it costs to keep one horse." Moreover, "it is fast enough and an excellent hill climber."

Metz continued to make cars — both in kits and fully assembled — at Waltham until after World War I, when the company's lackadaisical approach to business operations caught up with it. Plus, it might have suffered from some postwar anti-German feelings for the Metz name. Gone but not forgotten, Metz and his creations are still celebrated in Waltham with the Waltham Museum's annual Metz Day.