10 Of The Coolest Cars To Ever Break Land Speed Records

Speed is everything in the automotive realm, but if you're going to be record-breaking fast, you might as well look incredible while you're at it. Luckily, the aerodynamic demands of true speed beasts naturally sculpt them into some of the most striking designs ever to grace asphalt.

Many have gone through such extreme modifications that calling them "cars" almost feels like a lessened truth. Frankenstein rework or not, there's no denying that these marvels of automotive engineering are museum-worthy based on looks alone.

The land speed record has changed hands frequently between two major players: the U.S. and Britain. The latter is the current holder with the supersonic Thrust SSC. Both nations have raced across beaches and salt flats, hoisted fighter jet engines onto four wheel drives and bent the limits of physics, all in a relentless pursuit of the title: the fastest car in the world.

Don't expect production cars here. Sleek as they might be, those machines weren't engineered for Guinness World Record‑shattering speeds.

Thrust 2

At first glance, the jet-powered Thrust 2 suspiciously resembles the 1989 Batmobile, albeit draped in bright gold livery. But this is no superhero lift; it's the car that held the title of fastest in the world for 14 years, after Richard Noble piloted it to 633 mph on October 4, 1983.

A Rolls-Royce Avon 302 aero engine sits at the center of this car's tubular, lightweight, riveted aluminium panel chassis, churning out a staggering 30,000 hp. Flanking it are two drivers' cockpits, a design choice born from engineers' obsession with weight distribution. For cars this fast, even a slight imbalance could mean the difference between intactness and catastrophic flipping. Legend has it that, to offset Noble's on board weight, the team added a sack of potatoes, among other creative weight-balancing measures.

Running at 600 mph-plus is cool until it's time to stop safely. Thrust 2 solved this problem with a deployable parachute, accessible via a button on the steering wheel.

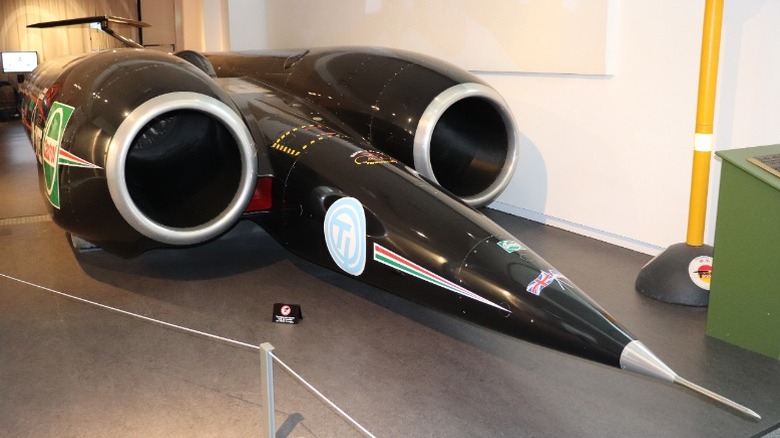

Thrust SSC

633 mph and a world record were apparently not enough for Richard Noble — afterward he began eyeing an even more audacious milestone: the speed of sound. Enter Thrust SSC, a jet powered aircraft he helped design alongside Ron Ayres, Jeremy Bliss, and Glynne Bowsher. On October 15, 1997, at Nevada's Black Rock Desert, it raced past 763 mph with Royal Air Force fighter pilot Andy Green at the wheel, claiming the title of the fastest car on land.

To break the sound barrier and keep the record firmly within British grasp, two Rolls-Royce Spey engines sandwiched the fuselage. Normally used in British F-4 Phantom II jet fighters, these turbofan engines delivered a combined 50,000 pounds of thrust, enough to give the Thrust SSC an astonishing 100,000 hp.

Also relied on was a precise aerodynamic shape that would make any eye gazing upon the vehicle easily mistake it for an aircraft; its tail even sported similar-looking vertical and horizontal stabilizers.Weirdly, the Thrust SSC's rear wheels were chosen as the sole steering mechanism. This unconventional concept was greenlit only after a Mini-Thrust SSC mock wheel test. 28 years later, the Thrust SSC still remains the only supersonic car in history... at least pending the materialization of the Bloodhound SSC's 1,000 mph dream. The Thrust SSC is displayed at the Coventry Transport Museum, alongside its predecessor, the record-breaking Thrust 2.

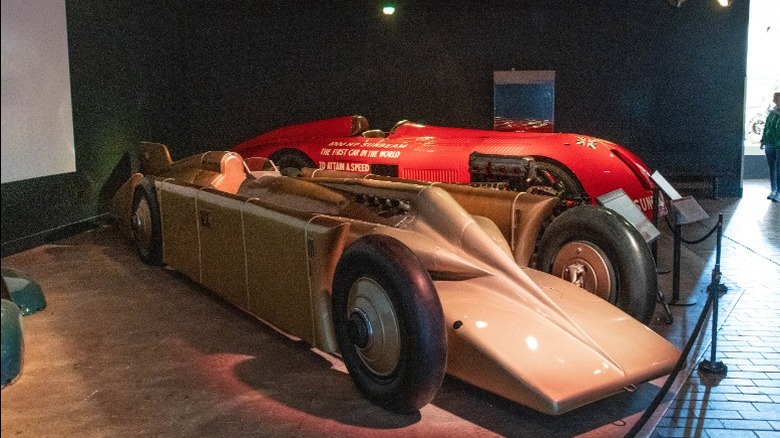

Sunbeam 1,000 HP

Pre-1927, talk of any vehicle hitting the 200 mph mark was unheard of, but the Wolverhampton-built Sunbeam 1,000 HP and driver Sir Henry Segrave changed the rules when they exceeded 203 mph on the sands of Florida's Daytona Beach on March 29, 1927. Central to this record were the two 22.5-litre Matabele aero engines audaciously crammed into the fore and aft of the vehicle, each churning 435 bhp.

It's quite ironic that the fastest thing on wheels of its time would be nicknamed "The Slug." Of course, the moniker had nothing to do with performance; just its long, rounded silhouette. Determined not to allow a car this legendary waste away while its engines and brakes were clogged in hardened oil, engineers at the National Motor Museum in Beaulieu, Hampshire began a rigorous process of restoration. They were guided not by manuals or documentation but by pure engineering knowledge and experience.

In September 2025, the engines were roared publicly for the first time in nine decades. The ultimate goal is to bring the car back to Daytona Beach in 2027 to commemorate the centenary of its record-breaking run. Don't expect another 200 mph-plus, though. A current speed limit at the beach sees to that.

Campell-Railton Blue Bird

The Slug had its moment, but some creatures (vehicles in this case) are simply born quicker. Campell-Railton's Blue Bird became the first car to break the 300-mph barrier, tearing across Utah's Bonneville Salt Flats on September 3, 1935, at 301.337 mph.

A product of Sir Malcolm Campbell and master engineer Reid Railton, this speed machine (also known as the Blue Bird V) was actually the successor to the slightly older but no less formidable Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird. That earlier version had already written its name in the record books twice, reaching 246 mph in 1931 and 251 mph in 1932.

To unlock greater speeds, the then-current Blue Bird was stripped of its Napier Lion VIID W-12 engine in favor of a Rolls-Royce R-type supercharged V12. The engine was bigger, heavier, and more aggressive than the previous occupant, so the bodywork had to be totally redesigned, becoming a full-width, slab-sided shape that covered the wheels and reduced drag. Raised ridges running along the top of the chassis accommodated the massive cam covers, twin rear wheels boosted traction on the sand and salt surfaces divided rear axle ensured smoother torque distribution. This piece of automotive history survives on both sides of the Atlantic: the original lives at the Daytona Speedway Circuit Museum in the U.S. and a replica is at the Lakeland Motor Museum in England.

MG EX181

One look is all it takes to understand why the MG EX181 was also known as the "Roaring Raindrop." Its aerodynamic chassis resembled that of an alien spacecraft with a tear or rain drop design.

The Ex181 existed in an era when MG Motors was still very much invested in the land speed competition. Rather than chasing the outright record — then held by John Cobb's Railton Mobil Special at over 400 mph — MG targeted the Class F benchmark. Class F refers to cars equipped with engines having a displacement between 1.1 and 1.5 liters. Juiced by a 1.5-liter twin-cam supercharged engine sourced from the production MGA, and with Stirling Moss behind the wheel, the Ex181 tore across the Bonneville Salt Flats on August 23, 1957 at a record 245.64 mph.

This car wasn't just fast, it was efficient, breaking 0.84 mph for every horsepower. Of course, much of that had to do with its incredibly-low drag coefficient (Cd), a measurement that describes how easily a vehicle slips through the air. The EX181 is widely believed to have achieved a Cd of around 0.12. For reference, most road cars fall between 0.20 and 0.50. Today, the "Roaring Raindrop" rests at the British Motor Museum in Warwickshire, England.

Bombshell Betty

Few race cars can claim an underdog rise quite as remarkable as Bombshell Betty's. What began as a stripped-out 1952 Buick Super Riviera was, in just three months, reborn by Jeff Brock and his team into a straight-eight land-speed challenger.

By the time the revamp was complete, Betty was a Buick only in name and chassis. Nearly every external surface and internal compartment had been transformed: custom-made windshield and panels, 1930s Chevrolet headlamp buckets repurposed as headlights, and a Ford 9-inch rear axle salvaged from a 1973 Thunderbird, among countless other alterations.

When dear old Betty arrived at the Bonneville Salt Flats for the 2009 Speed Week, she looked anything but pretty. She had a sort of bizarre, rough-edged coolness to her, just not the kind most onlookers would peg as race-ready. However, when her tyres rolled, they did so at 130.8 mph, crushing both the XO class and the GCC class records. Over the next few years, Betty only got quicker, setting records in 2010 (141 mph), 2012 (162.4 mph and 165.3 mph), and again in 2013 (165.7 mph).

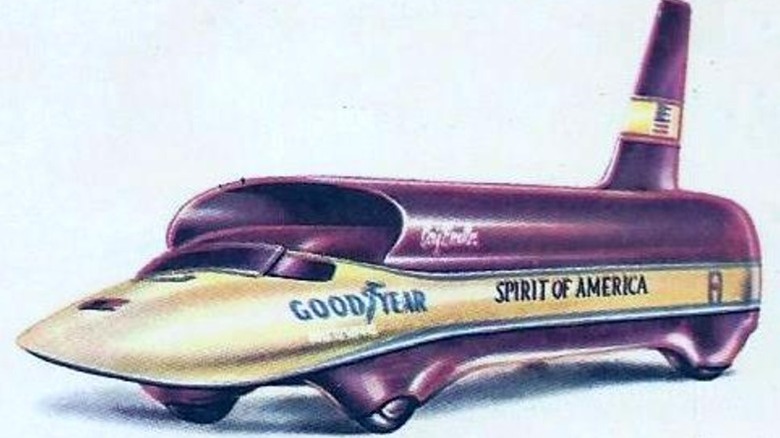

Spirit of America Sonic 1

Craig Breedlove's 1963 Spirit of America may have launched the jet-powered car era and taken the concept a bit too literal, but competition was watching and quickly snatched the 400 mph and 500 mph records it and its successor had set.

Sonic 1 had to keep the land speed record firmly in the hands of America, and thus eyed the 600 mph milestone. With a fuselage-like body stretching over 34 feet, it looked less like a car and more like an aircraft laid horizontally across the salt flats. Spitting raw thrust the back was the gaping nozzle of a General Electric J47 turbojet engine that usually called U.S. Air Force strategic bombers and fighter jets home. The J47 drove the car with pure propulsion, meaning that Sonic 1's wheels had no mechanical link to the engine.

Decades after shattering records, Sonic 1 finally crossed the auction block in March 2025, fetching $1.3 million.

Blue Flame

If the Spirit of America Sonic 1 is a jet on wheels, its nemesis is a four-wheeled rocket. Conceived by Keller and Ray Dausman of the Illinois Institute of Technology, the Blue Flame's three-phase rocket engine combined hydrogen peroxide and liquefied natural gas, pressurized with helium, to generate 58,000 hp and 22,000 pounds of thrust.

The result of the Blue Flame's 6,500-pound weight and Pete Farnsworth's 37-foot long aluminum-skinned chassis was a speed record of 622.4 mph, which it achieved on October 24, 1970, with Gary Gabelich at the wheel. It did take over 24 test runs to achieve perfection, but Bonneville had, and still has, never seen a machine move faster. In other words, the Blue Flame remains the fastest American land-speed car ever.

Even when Richard Noble's Thrust 2 shattered it thirteen years later, few would argue that it looked anywhere near as cool as the Blue Flame.

Bluebird CN7

The Bluebird CN7's bodywork is almost as remarkable as the 403.10 mph world record it set on July 1964. Like all other insanely fast cars, its chassis was designed to be durable yet lightweight and aerodynamic enough to reduce drag as much as possible. To achieve this, the designers used lightweight aluminium honeycomb panels.

But its path to becoming the fastest car in the world, and even after, was anything but smooth. For starters: the cost. It cost Motor Panels Ltd a whopping £1 million (around $1.3 million) to put the car together! The Norris brothers, Ken and Lew, selected a Bristol-Siddeley Proteus gas-turbine engine capable of delivering over 4,000 hp. It's a power unit more at home in aircraft than on wheels.

Yet power alone was enough to guarantee success. The Bluebird CN7's first record attempt in 1960 ended in near-fatality for Campbell, who sustained minor injuries, and fatality for the Bluebird, which was destroyed. Four years and two failed attempts later, it reached the record speed of 403.10 mph, thanks to the signature vertical stabilizing fin. However, no sooner would the CN7 set a world record than it would be surpassed. The age of jet-powered cars coincidentally became legal and official in 1964, meaning that competitors took no time slamming these on racecars and leaving Campell's record in the dust.

Irving-Napier Golden Arrow

Another one of Sir Henry Seagrave's bold bids for land-speed supremacy, the Irving-Napier Golden Arrow was engineered with a single purpose: to win Britain back the record it had briefly held in 1927 and 1928. Its compound first name honors its designer, Captain J.S. Irving, and the Napier W12 Lion 23.9-liter engine that powers it.

The Golden Arrow was a sharp, gold-toned dart of a machine, resembling a Batmobile in more ways than one. Every line of its bodywork served an aerodynamic purpose. The car sat incredibly low, and its rear wheels were powered through two separate prop-shaft tunnels, heavily reinforced in case of catastrophic failure at speed. So committed was the Golden Arrow to its purpose that the engineers bothered less to include a differential gear since a dead-straight run was all that was hoped for.

The number to beat was 187 mph, set by America's Ray Keech and his "Triplex Special" in 1938. And on March 11, 1929, on the sands of Dayton beach once again, Segrave took the Golden Arrow past 231.446 mph.