Chevy's 327 Proved You Don't Need A Big Block To Win Races

American automotive performance in the 1950s was a simple recipe. If you wanted to go faster, you didn't optimize what you had; you just added more to it. More displacement, more iron, more horsepower, and more weight — all of which was preferably hanging over the front axle. This, as you can imagine, resulted in cars that were blisteringly quick in a straight line, but handled corners like a cruise ship. The entire trajectory of attaining more power was anchored on an increase of cubic capacity.

Then, one man and one tiny V8 came along to fundamentally rewire Detroit's brain. You can't tell the story of the revolutionary 327 small-block Chevy (SBC) without starting with its architect, Edward N. Cole. Born in Michigan, he started his career climbing the engineering ranks at GM, culminating in a stint at Cadillac where he was the one responsible for its groundbreaking 331 cubic inch overhead valve V8. When Chevrolet brought Cole on as its chief engineer in 1952, he arrived with a single, effective design mandate: The future of Chevy power had to be compact. He promptly scrapped whatever tired V8 project was lingering on the company's drawing boards at the time, and his team started from scratch to pave the way for the most powerful Chevy small-blocks ever made.

The original genius of simplicity

The result of Cole's demand for simplicity arrived just three years later, when his team delivered the foundation for the 327. The then-new 265 cubic inch small-block was a master class in low-cost engineering. Cole's team used a green-sand casting process that let the block be molded in an inverted position, a change that streamlined production and reduced the amount of machining required. Crucially, they went with lightweight, stamped-steel rocker arms, a seemingly budget-cut move, but one that let the valvetrain cope with far higher engine speeds.

The internal design was equally smart. The new cylinder heads featured highly efficient cross-flow ports and wedge-shape combustion chambers, and was secured with improved cylinder-head sealing. Components were tightly integrated, with an intake manifold that bundled the coolant passage, distributor mount, and the lifter-valley enclosure into one casting, tightening the whole package considerably. The block also did away with external oil lines for internal ones, instead employing the hollow pushrods to supply oil to the heads. This compact layout allowed the new V8 to come in roughly fifty pounds lighter than Chevrolet's old Stovebolt Six.

The combination of its compact size, light weight, fuel-efficiency that was comparable to six-cylinder engines, and its incredible power density quickly earned the engine the nickname – "Mighty Mouse." This engine would go down in the history books as an icon that powered more cars than any other. The small, light, and cheap performance engine had arrived. But the 265 was just the setup. Its perfected vision, the 327, was waiting just around the corner.

The Mighty Mouse peaks perfection

The 327 arrived in 1962, and it wasn't just a bigger engine. Cole's ingenuity had prompted a shift in Chevy's mindset, so the engineers didn't simply add displacement haphazardly. The 327 cubic inch displacement was achieved by giving the small-block a 4.00-inch bore paired with a longer 3.25-inch stroke. This change created the sweet spot for high-RPM operation. Its options included higher-powered versions, as four-barrel carburetors and compression ratio tweaks pushed outputs ranging from 250 to 340 horsepower. The Corvette versions equipped with Rochester mechanical fuel injection were especially potent, producing around 360 horsepower thanks to their aggressive 11.25:1 compression setup.

The 327's absolute peak arrived in 1965. With a four-barrel Holley carb, it hit 365 horsepower, but the Rochester Ram-Jet fuel injection system cranked the output up to 375. This made for a commendable 1.146 horsepower per cubic inch. When the 396 big block arrived later in the same year, the 327 was forced to take the back seat. But it remained as the Corvette's high-performance backbone, offering configurations up to 350 horsepower until 1969. The 327 was definitive proof that size doesn't matter as much as smart design.

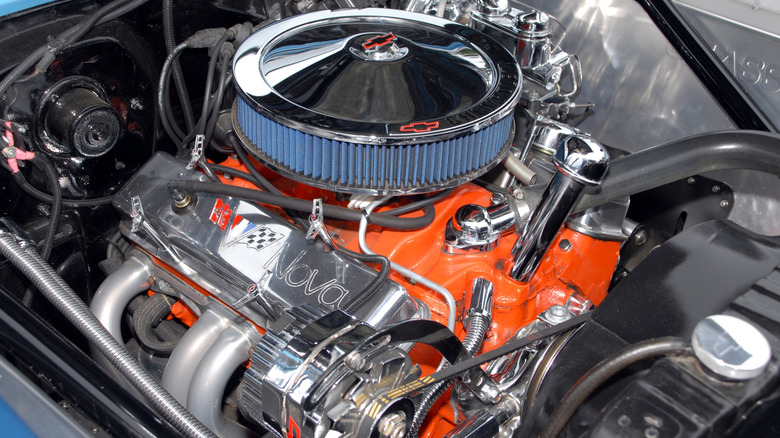

The L79 and the cult of the camel hump

Peak horsepower figures are great for headlines, but the real-world hero of the 327 family was the L79. Introduced in 1965, this 350 horsepower package earned a reputation not just for its power, but for just how easy it was to live with. By ditching the fussy solid-lifter cam in favor of a hydraulic setup, the engine suddenly demanded far less fiddling from weekend wrenchers. That change alone made the L79 a favorite among younger racers who wanted to run hard without pesky maintenance. In cars like the 1966 Nova SS, the engine transformed an otherwise mild compact (although, the American Compact Car was pretty big 40 years ago) into a fast and practical muscle car that stayed competitive through the late '60s.

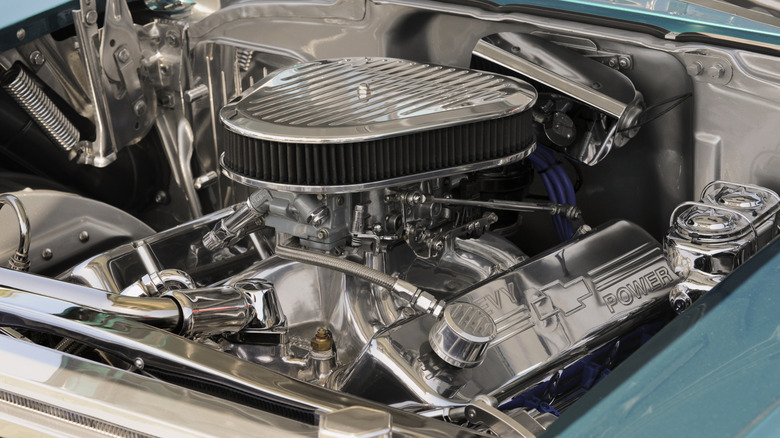

The true tuning potential of the 327 was in its top-tier cylinder heads. The high-flow castings used on the stronger variants became famous in their own right, especially on the fuel-injected Corvettes that inspired the "fuelie" shorthand still used by enthusiasts today. These heads breathed far better than most small-block castings of the era, which is why racers sought them long after the factory stopped their production. Their trademark casting bumps, long known in enthusiast circles as the "camel hump," became an instant visual giveaway that the engine carried performance-oriented heads.

You could confuse the name with the weird four-seat Corvette with its humped-back roofline that never made it to production. But that car was Cole's idea, so no prizes for guessing the possible inspiration behind it. Even today, builders still chase that retro aesthetic and airflow potential, with modern companies offering aluminum reproductions that capture the look while improving durability and performance.

The eternal legacy of the SBC

The real measure of the 327's genius is the seismic shift it caused in amateur racing and hot rod circuits. When it debuted in 1955, the new Chevy engine was a remarkable design triumph. It weighed in at about 531 pounds, much lighter than V8s of the time and Chevy's earlier inline-sixes. This low mass was the first philosophical victory, setting the stage for decades of performance dominance.

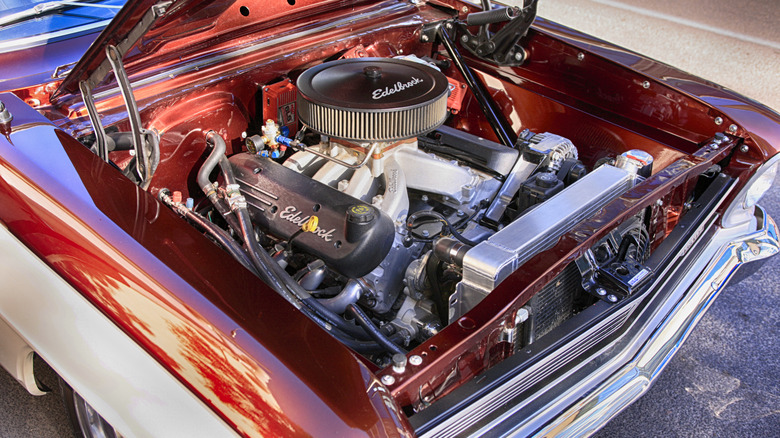

The engine's legendary status however, was not cemented on the factory floor, but in the garages of Southern California. Chevrolet strategically shipped three early blocks to hot rod pioneer Vic Edelbrock. Edelbrock immediately showed the SBC's potential using simple swaps involving a three-two-barrel intake alongside custom-made exhaust headers and ignition, all coming together to hike the output by 50 horsepower. Cam grinders like Ed Iskenderian further unlocked the engine's rev potential, pushing the redline from 5,000 to 6,500 rpm. The modular, accessible architecture made the SBC the definitive hot rod engine, quickly displacing the Flathead Ford. This early aftermarket frenzy eventually led to a sprawling performance ecosystem.

The 327, particularly the L84 with fuel injection, remained at the pinnacle of Chevy's small-block performance for many years. The foundations laid in 1955 for compact design and simple engineering were the ultimate recipe for enduring performance.

The 327's racing dominance

The 327's influence reached a turning point in the late 1960s, when Chevrolet needed a legal engine for the Trans-Am road-racing series hosted by the Sports Car Club of America. The rules capped displacement at five liters, and Chevy didn't have an off-the-shelf option. So, engineers mixed and matched the existing small-block components. Using the 4.00-inch bores of the 327 block and pairing them with the 3.00-inch crank from a 283, they created a 302 cubic inch engine designed to scream at high rpm. That motor became the centerpiece of the now-iconic first-generation Camaro Z28, homologated specifically for Trans-Am competition.

This parts-bin perfection approach would influence Chevrolet's engine program well into the 1980s. The 302's success demonstrated that the small-block's core architecture was modular enough to build new displacements simply by swapping bore and stroke combinations. This spawned engines like the 307, which effectively flipped the 302's formula by pairing the 327's longer stroke and 283's smaller bore. It was the small-block's adaptability that kept it competitive across multiple racing disciplines.

But if one name cemented the 327's drag-racing legacy, it was Bill "Grumpy" Jenkins. He became nationally known in the early 1960s for campaigning a string of supremely effective "Old Reliable" Chevrolets in Super Stock and Factory Experimental classes. When he returned to Chevrolet in 1966, after a brief stint driving Mopars, his first new machine was a 327-powered Chevy II, rated at 350 horsepower. That early 327-powered "Grumpy's Toy" became the foundation for his eventual status as the "Father of Pro Stock," and much of his later development work defined how the small-block evolved for racing use.