4 Misconceptions About Hybrid Engines (And What's Actually True)

Modern hybrids have been helping folks save gas for about 25 years at this point, with the first mainstream model, the Toyota Prius, launching in Japan in 1997. Yet, even after a quarter of a century, there are still some common myths and misconceptions about what hybrid power actually does for your car.

Take the Prius itself. Many people think it's literally the first-ever hybrid car, but that's not the case. The first car to combine electric battery power and a gas engine was actually the Lohner-Porsche Elektromobil, which premiered at the Paris Exposition in 1900. And yes, the Porsche part of the name does refer to Ferdinand Porsche — while the Elektromobil designation came from the fact that it was engineered to be a pure EV. It was Porsche who had the idea to use a gas-engine to recharge the batteries on the go, meaning the company has been (sort of) building hybrids for 125 years.

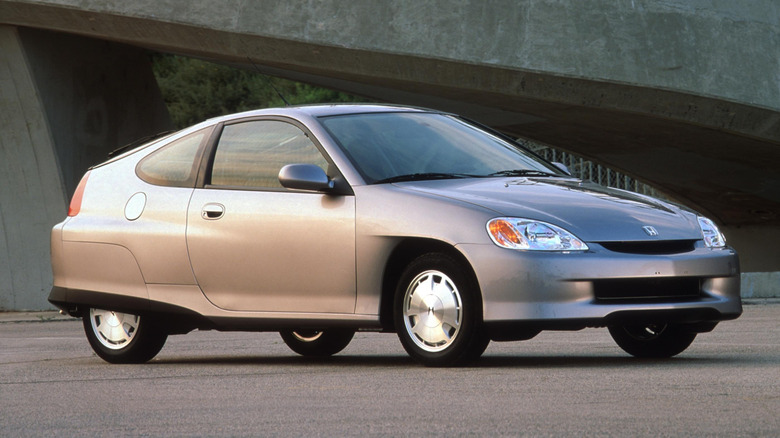

Nor was the Prius the first hybrid available in the United States. The honor of launching America's first hybrid goes to Honda. That company started selling the first-gen Insight in the U.S. at the tail end of 1999. The Prius didn't make it here until 2000 as a 2001 model.

What else is fact and what's fiction about hybrid engines? Let's bust some myths to find out!

Myth: Hybrids have to be plugged in

Many people believe that buying a hybrid car means you have to plug it in all the time to keep the battery charged. It's easy to understand the confusion here, because there are cars specifically called plug-in hybrids. However, they're different from traditional hybrid vehicles — and, FYI, they may not help drivers move toward EV adoption after all.

Nearly all cars on the road today — even non-hybrids — require some amount of electricity to operate. A gas-only car, for instance, typically has a 12-volt battery to run the starter and spark the engine. A hybrid adds a larger additional battery and can leverage its electricity to help take some of the load off the engine itself.

And while the extra electricity delivers enough extra power for a noticeable bump in fuel economy, it's not enough to require plugging in. Instead, a hybrid vehicle recharges with regenerative braking, which creates energy by capturing the motion of the spinning wheels while also slowing the vehicle down. Plug-ins and EVs need to connect to an external power source because regenerative braking can't produce enough electricity to keep their bigger batteries filled.

Myth: Hybrids cost more to maintain and repair

This one is a bit tricky because of how expensive it can be to replace the hybrid system's battery. If you need to do that, it will take $2,000 to $8,000 to buy a new one, and another $500 or so to install it. We're talking serious coin, but there's also a good chance you'll never have to pay out. All automakers must provide warranty coverage for hybrid batteries for at least eight years or 100,000 miles, per a federal law, and some, like Toyota, go even further. This brand backs its hybrid batteries with 10-year/150,000-mile coverage.

As for more routine maintenance and repairs, having a hybrid can actually reduce your expenses. After all, since neither the gas engine nor the traditional brakes work as hard in a hybrid as in a gas-only vehicle, those components undergo less wear and tear –- which could mean fewer failures and replacements. Note that this doesn't mean you can simply ignore things like oil changes, spark plug replacements, and services for drive belts and hoses. Remember, the traditional powertrain is still there and still needs to be in top condition to operate properly.

Myth: Hybrids only save fuel in the city

Although hybrids give a bigger boost to fuel efficiency in urban areas than on the highway, that doesn't mean you won't notice any improvement on the open road — it isn't a zero-sum game where better efficiency in one scenario necessarily means worse efficiency in the other.

It's just that the typical hybrid system is primarily there to help give the engine a boost when accelerating from a stop, and the battery gets its energy to do this from braking. Considering these features and how frequently drivers brake and take off from a stop while navigating urban environments, the discrepancy between city and highway mileage starts to make more sense. On the expressway, on the other hand, the engine doesn't need a short-term boost to keep you at a steady cruising speed. In addition, you may not have to even touch the brake pedal for long periods of time, eliminating the chance to regenerate electricity.

For a real-world example, consider what we called the best minivan ever. It's the Kia Carnival — which the brand refers to as a multipurpose vehicle, or MPV — and it's available with or without hybrid assistance. Without, the Carnival scores EPA ratings of 18 mpg city/26 mpg highway/21 mpg combined. If you prefer your Carnival rides with hybrid help, you can enjoy an EPA line of 34/31/33.

Myth: Hybrid cars aren't fun to drive

With fuel-sipping hybrids like the Toyota Prius, the powertrain concept is to add some electric motivation to the car so that the gas engine doesn't have to run as hard or often — which saves gas. But you can also use that electric energy to boost the efforts of the engine rather than reducing them. This is the idea behind thrill machines like the hybrid McLaren W1 hyper car, the Porsche 911 Turbo S T-Hybrid, and the V6-Powered Hybrid Ferrari F80. You better check with a cardiologist if one of these machines doesn't get your heart pumping.

Of course, if you're looking for enhanced efficiency, you should probably look elsewhere. Finding official fuel-economy numbers on these new sports cars isn't easy, but Porsche claims that the 911 Carrera GTS can achieve between 21.4 and 22.6 mpg combined in Europe's WLTP testing regimen with the T-Hybrid setup.

It's true that the WLTP ratings don't translate directly into EPA grades, but for comparison's sake, the all-wheel-drive Honda CR-V has a WLTP rating of 35.1 mpg combined and 37 mpg combined according to the EPA. The flipside to this is a 0 – 100 kph time of 3 seconds, with a top speed of 194 mph, for the Porsche, compared to times of 9.4 seconds and 116 mph for the Honda.