Planes Use Rivets But Cars Have Welds: Here's Why

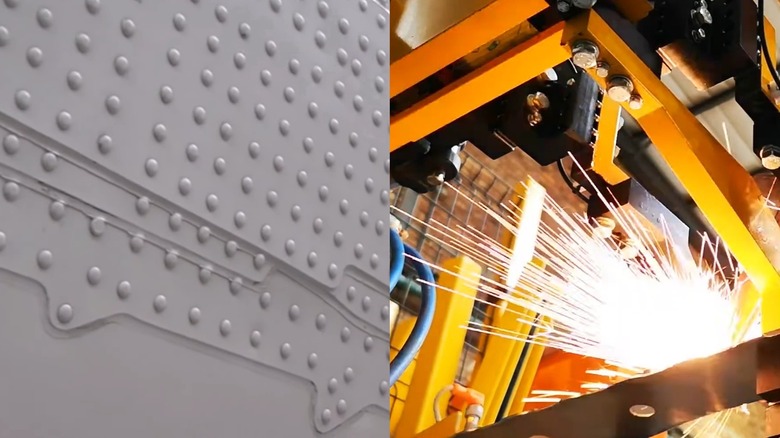

One of the oldest ways to attach materials together, the rivet goes back thousands of years to the pyramids of Egypt. A modern rivet is a metal fasteners with a rounded head on one side, and a narrower, smooth bolt-like stem on the other. It's inserted through a hole in multiple pieces of metal, and a hammer or rivet gun reshapes the stem or "tail," preventing it from backing out. This tightens the metal pieces together, with a larger diameter head on either side creating a permanent bond.

As technology advanced, by the 19th century larger structures, massive naval vessels, and lengthy rail lines required rivets, making them the go-to option for works such as the Eiffel Tower and, less enduringly, the Titanic. In fact, some have speculated the doomed ocean liner had unreliable rivets, and that's why the Titanic sank.

According to the rivet company Rivetwise, rivets held together most of the 22,000-plus miles of train track that spanned in Great Britain by 1900. They also had, and have, a strong relationship with aviation. Rivets are ideal for providing a lasting solution to the unique stresses of an airplane, withstanding immense pressure without cracking.

Welding also can be an incredibly strong option for joining materials, and is used heavily modern skyscraper structure reinforcement and the automobile industry. However, aluminum welded joints aren't nearly as strong as the ones secured by rivets, the aluminum used to make aircraft doesn't react well to heat, and automobiles typically use a different type of metal that welds together much better.

If rivets are stronger, why don't automakers use them exclusively, too?

Unlike the aviation industry, which relies on aluminum, automakers construct vehicle frames primarily using steel. Welding steel parts together properly is much easier than attempting to do so with aluminum and provides a robust bond. This is because steel has a higher melting point, making it less sensitive during the process, while aluminum must be meticulously monitored to ensure weld integrity.

Aircraft that incorporate composite material in place of some aluminum also can't tolerate the heat of welding. Due to steel's more heat-forgiving composition and the fewer steps required to weld, welding also translates well into highly automated mass-production operations such as automotive assembly lines. It can come in handy for single project builds, too, like a V8-swapped Chevy Sonic.

If you decided to use rivets on a car instead of welds, it would also be heavier. Rivets can require supporting plates, in addition to however many multitudes of the metal fasteners themselves. Reducing a vehicle's weight can improve both performance and fuel efficiency, because the engine isn't required to move as many pounds. But wait; aren't aircraft engineers also concerned about weight? Yes, but rivets are worth the tradeoff, as welds just can't hold up equally under the same conditions, potentially resulting in structural failure several thousand feet off the ground.

Lastly, while rivets are a common sight in aircraft designs, it's doubtful automakers would want to compromise their vehicle exteriors' sleek lines with hundreds of visible bumps. In fact, car makers go to great lengths to hide materials' joints in places tucked behind their creations' visually clean surfaces.