This Internal Combustion Engine Didn't Need Oil, At Least On Paper

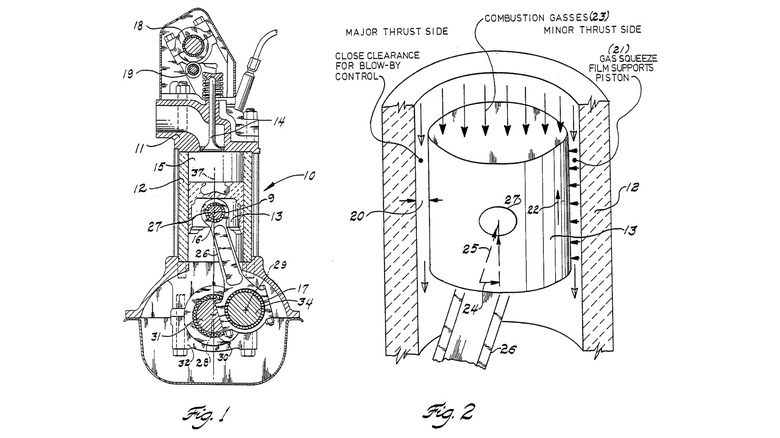

Ford once sketched a road where an engine's pistons never saw oil and engines ran hotter on purpose. In a late‑1980s patent application filed and granted in Europe, the company described an "uncooled oilless" internal combustion engine. What it did was replace the liquid film that lines conventional oil-cooled cylinder walls in a piston engine with a cushion of gas. The idea was simple in theory, but radical to execute. If you can keep a razor‑thin gap between the piston and the cylinder wall, and use the motion of the piston to drag air through carefully shaped grooves, you can build a self‑pumping "gas squeeze film" that separates the moving parts.

The patent even specifies the use of ceramic components (including the cylinder head, cylinder walls, pistons, and valves) with low thermal conductivity so that the engine retains heat and operates efficiently at high temperatures. In short, less parasitic losses, fewer fluids, and a cleaner burn, at least on paper. The filing describes ringless pistons, micron‑level clearances around one‑thousandth of an inch, and step‑like features that shape airflow into a pressurized cushion as the piston travels. If the parts are perfectly straight, they'll hold that tiny gap, and the gas film does the work oil would usually handle.

The catch, as always, is in the details. Modern engines use oil for more than lubrication. It also cools and cleans the engine. Engine oil additives like Seafoam and Lucas help in some cases. Replacing all of that with air and ceramics would demand a new way to build engines from the inside out.

How Ford's gas‑phase engine was supposed to work

The patent application calls for high‑stiffness, low‑conductivity ceramics like sintered silicon nitride, silicon carbide, and partially stabilized zirconia for pistons and liners. That recipe limits thermal expansion and keeps heat inside the combustion chamber. Then comes the construction. Instead of the piston rings, the piston itself and the cylinder bore get preshaped to have a radial taper. As the piston travels, viscous drag pulls air into the gap. The tapered shape compresses that air locally, creating a uniform pressure field that supports the piston on an air cushion thousandths of an inch thick.

The application anticipates pressure differences, too. During the exhaust and intake strokes, the gas film is weak as the pressure feeding it is low, so the design leans on ultra‑smooth finishes, controlled clearances, and hard, wear‑resistant surfaces to survive brief metal-on-metal contact periods, say during cold starts. Once the engine reaches operating speed, the gas cushion carries the load and the blow‑by drops to very low levels (less than 2% of the flow above 1,500 rpm).

With no piston rings and no oil control tasks, friction falls. With an uncooled block and head, the engine retains heat and theoretically converts more of it into useful work. The net promise is fewer losses and simpler plumbing. On paper, you end up with a hotter, leaner, cleaner machine that sidesteps oil's messy use and added manufacturing complexity.

Why the oilless idea never left the lab

Reality bit hard. Holding a fine gap between a hot piston and hot cylinder is a metrology nightmare. The tiny clearance gap between the piston and cylinder wall is key to keeping the piston aligned, reducing friction, and preventing blow-by, but it constantly shifts with heat, engine loads, and other forces that engineers must carefully manage. Ceramics are strong, corrosion-resistant and heat‑tolerant, but they're expensive to machine, and achieving high-micron tolerances can be costly. Ceramics can also be unforgiving under impact loading and damaging to the environment during extraction and waste handling.

The gas film is engine-speed‑dependent, so start‑up and idle are danger zones when metal-on-metal contact is most likely. The effect is similar to engine oil pressure altering due to viscosity changes on colder and hotter days. Dirt or carbon in that microscopic gap can score surfaces that won't be easy to repair. And the rest of a modern engine still wants oil for cooling components, driving variable‑valve gear, operating hydraulic tensioners, and carrying away debris. Modern oils are getting thinner but are still necessary for engine functioning.

There's also the heat problem. An uncooled, low‑heat‑rejection engine runs very hot, up to 1,600 degrees. The challenge lies in figuring out how to make gas-phase lubrication work reliably while dealing with thermal expansion, changing tolerances, and the absence of traditional oil lubrication. The manufacturing challenge sits atop that: The tolerances and finishes required are achievable, but reaching them cheaply at scale is another story.

That's why this concept remains a fascinating branch on the engine-family tree rather than the trunk. The patent expired years ago, and the fully oilless auto engine never arrived. But the research still nudges how engineers chase lower friction and higher efficiency.