How Electric Vehicles Like Tesla's, Ford's & GM's Keep Batteries Cool

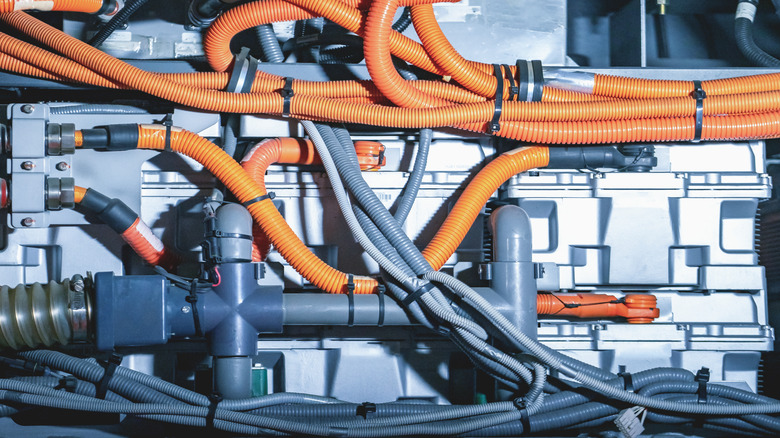

EV battery cooling tech has come pretty far in the last 30 years. The GM EV1, for instance, was reengineered in 1999 with an air tunnel to properly cool its optional nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) batteries, but it still couldn't be sold in Arizona because the battery still got too hot. Now, however, we have advanced cylindrical, prismatic, and pouch-style lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries with liquid cooling (typically ethylene glycol, a.k.a. antifreeze) and active air solutions to handle environmental extremes — even in Arizona.

Passive air cooling, as seen in the original Nissan Leaf, is simple and cost-effective, but its cooling ability is limited. Active air cooling employs fans or chilled air from the HVAC system, and is still the method used by the Lexus UX300e, though indirect liquid cooling can better tackle current EV power levels. Direct liquid cooling isn't used for consumer EVs because the batteries would need to make, well, direct contact with a liquid, and it would need to have zero electrical conductivity to avoid shorting the battery.

Most EVs use cold plates (also called cooling plates), which feature coolant passages strewn through a flat sheet of metal adhered directly to the bottoms of battery cells. Cold plates are usually made of aluminum alloy, stainless steel, or copper and can cool one pack of cells or two. Rivian, Hyundai, Ford, GM, and Lucid all use cold plates. Tesla, on the other hand, routes coolant pipes throughout the cells, which may be done so that its 4680 batteries can vent from the bottom in case of thermal runaway, or to be different and make this article longer.

Tesla cools from the side, everyone else goes for the bottom

Tesla's battery cooling has undergone quite a few revisions to improve temperature regulation of its cylindrical cells. In the Model S P85D, one coolant path chills 444 cells. The problem is that coolant gets quite warm by the end of its journey, especially given how many cells it must handle. So, for the P100D, Tesla switched to two paths that each cool 258 cells. In the Model S Plaid, 11 individual coolant pipes are responsible for just 144 cells each. Coolant passages also changed from being relatively straight up to 2017, meaning they contacted a small portion of each cell's side, to serpentine in 2018, dramatically improving the contact patch.

While Tesla has refined intra-cell piping, cold plates have two big advantages. First, cold plates allow the battery to have more cells packed horizontally. Second, as Peter Rawlinson of Lucid told Auto Evolution, cold plates in the remarkably quick Lucid Air Sapphire cool the battery more efficiently since they contact the bottom of the cell, or the anode, where much of the heat builds up. Either way, temperature monitoring ensures the battery stays in a safe, usable range.

Each automaker employs cold plates in its own way. Lucid uses a super-thin layer of adhesive to join the cells to each cold plate for the best possible thermal conductivity, while the Hyundai Ioniq 5 uses a comparatively thick adhesive that results in more distance between the cells and the plate. However, the Ioniq 5 also uses one massive cold plate rather than individual plates for each battery pack. Rivian uses cold plates too, but sandwiches them between the cells to cool two layers at once.

Some like it hot

The Hummer EV, a vehicle larger than some buildings, places cold plates on top of individual battery packs in a gargantuan steel enclosure. These cold plates can become hot plates, warming the battery to the optimal temperature range when entering Watts To Freedom (WTF) mode, unlocking the full 1,000 hp. The Hummer's heat pump also chills the motors for peak efficiency.

Ford's F-150 Lightning also uses cold plates, but places battery packs in aluminum enclosures rather than steel. Not only is aluminum lighter, but it's more efficient at dissipating heat. Of course, the Hummer EV 3X doesn't care about the weight of steel because it makes 1,000 hp and a ridiculous 11,500 lb-ft of torque, if you listen to marketing, or a more realistic but still insane 1,000 to 1,100 lb-ft (if you go by Road & Track and Autoweek's reporting).

If a Hummer EV is like winning the torque Powerball, an extended range Ford F-150 Lightning at 580 hp and 775 lb-ft is still like winning a $500 a week for life scratch-off. Incredible, but not quite in the same power ballpark. Plus, if Hummers have to heat the battery in WTF mode anyway, steel's thermal properties might be irrelevant. Strange how the Hummer EV is the least efficient EV you can buy.

The huge variety of cooling solutions is mind-boggling, and detailing every system would result in a Dostoyevsky-length novel. The gist is that passive air cooling has gone the way of dodos, active air cooling is almost extinct, and liquid cooling is the still-thriving dominant species. Still, like Galapagos finch beaks, there's still plenty of micro-evolution happening, like GM's U-shaped prismatic batteries, and we have yet to see which changes help EVs adapt to our world the best.