Why V Shaped Engines Can't Use Just Any Angle

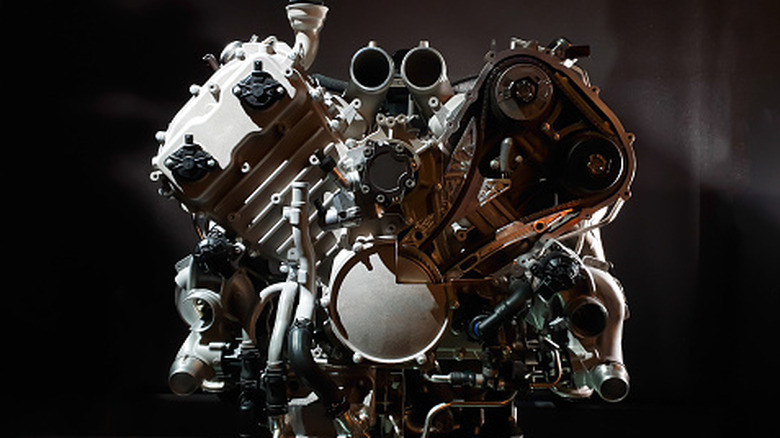

In an internal combustion engine, air and fuel are injected into the cylinders, where ignitions occur in a controlled environment. The combustion cycles force pistons to move, and that movement is channeled through the crankshaft and the transmission to rotate the wheels. The fact that cars move with just a mild vibration and a pleasant sound that varies from engine to engine comes in great part from using the right angle between cylinder banks.

First, imagine one cylinder at work: combustion pressure pushes the piston inside the cylinder and turns the crankshaft. Then the piston is moved up, down and up again until the next combustion cycle because of the crankshaft's rotational inertia. The reciprocating movement of the piston's mass with alternating acceleration exerts an inertial force along the cylinder's axis with alternating direction. That force is transmitted through the engine block and generates a dynamic load against its mounts.

Automotive engines use multiple cylinders to produce the desired power and torque, optimizing weight distribution and smoothness. But if they all worked in perfect synchrony, they would simply generate more of the same dynamic load — power and torque would be delivered in pulses, right after the ignition, making the engine behave too roughly.

The solution is balancing those forces, which engineers do with two resources. One is timing the cylinders so they fire at equal intervals until the first one fires again. The other is arranging cylinders in two banks with an angle, the V configuration. Since more cylinders implies more forces to balance, that angle depends on the number of cylinders. For example, the angle for V8 engines is usually 90 degrees; other angles would make those forces unbalanced and generate undesired motions that could even damage the engine.

The optimal angle is related to cylinder firings and piston movement

The mechanical stress caused by a combustion cycle has three main sources. One is the firing force from the combustion cycle. Instead of having all cylinders fire together, it's possible to balance them by evenly spacing the firing of each cylinder within 720 degrees, which is the crankshaft's spin during two combustion cycles. In a four-cylinder engine, for example, we have 720 degrees/4, or 180 degrees: the engine should fire one cylinder at every 180 degrees of the crankshaft's spin.

The next source is the crankshaft's rotational inertia, aided by counterweights to balance the piston's movement. Finally, the third source is the piston's reciprocating force from moving inside the cylinder. Engineers align the angle between banks with the firing interval because that configuration is naturally balanced. With different angles, piston and counterweight forces would peak at different moments, causing imbalance and a rocking motion on the engine.

Boxer engines can be seen as an extreme V configuration whose angle between banks is 180 degrees. They are naturally balanced when they have an even number of cylinders: by timing each bank to move exactly opposite to the other, the forces of half the cylinders naturally cancel out the others.

Moving on to the V8, the trick is to see it as four V2 engines bolted together. First, we calculate the firing interval: 720 degrees/8 = 90 degrees of the crankshaft's spin. Now, by aligning that firing interval to a 90-degree angle between banks, it's possible to balance cylinder pairs from opposite banks (that concept of four V2s) with the crankshaft's counterweights at every 90 degrees of rotation. That construction helps achieve balance in a V8 engine.

Other designs are feasible, but require additional resources to work

Inline engines can be viewed as another extreme V configuration, but with 0 degrees between banks. Setting the firing interval to that angle isn't viable because it would cause that pulsating power and torque delivery. Using equal firing intervals helps, but the engine ends up exerting end-to-end vibration on the crankshaft. An inline-3, for example, requires a balancing shaft, an additional part designed for that purpose.

For V6 engines, the firing interval should be 720 degrees/6, or 120 degrees. Applying that bank angle would make the engine excessively wide, so engineers chose 60 degrees, exactly half, to keep the firing forces balanced. However, because each bank has an odd number of cylinders (three), their reciprocating forces cannot be perfectly balanced as seen above, and a balancing shaft becomes necessary.

Speaking of V6 engines, some designs use 90 degrees between banks, usually adapted from V8 engines. Their solution is different: a split-pin crankshaft that essentially alters the cylinders' firing interval to match the ideal 120 degrees. That's another example of what happens when the cylinder banks have a different angle from the ideal one: the engine ends up imbalanced and requires extra parts to address the issue.

Automakers have tried many other solutions over time, of course. Some of the most notable are Volkswagen's VR6 engine, whose angle is just 15 degrees in order to reduce size and use a single cylinder head, and the V10 used on the Dodge Viper, which was sadly discontinued in 2017. That engine uses a 90-degree angle like a V8, but fires unevenly on purpose in order to get its distinctive sound.