How The Civil Air Patrol Became America's Quietest Aviation Power

When most people picture U.S. airpower, it's the obvious stuff: fighter jets slicing the sky or massive cargo planes swallowing tanks. Nobody's thinking about a gray-haired engineer from Poughkeepsie flying an old Cessna 172. But that Cessna? It's part of the biggest fleet of single-engine piston aircraft in the world, run by volunteers. And those volunteers save, on average, more than 100 lives a year.

Not glamorous, but effective. Proving the old adage, it's not always about having the biggest or flashiest tool for the job — it's about having the right one. And in this case, sometimes that tool isn't an F-35 screaming past the sound barrier, but a Cessna 172 trundling along. Quiet, unglamorous, maybe even overlooked — but exactly what the mission calls for.

The Civil Air Patrol is the Air Force's official auxiliary. It's been around for more than 80 years and operates in a weirdly wonderful space between a civilian flying club and a full-blown military partner. Over that time, it's done everything from chasing Nazi subs to snapping the first aerial shots after hurricanes. Somehow, it manages to stay mostly invisible. Quiet, but dependable.

So how did a nonprofit powered by enthusiasts become such a vital piece of the national security puzzle? The answer involves a story so outrageous, it's shocking no one's made a movie about it — yet.

It all started with hunting Nazi U-boats

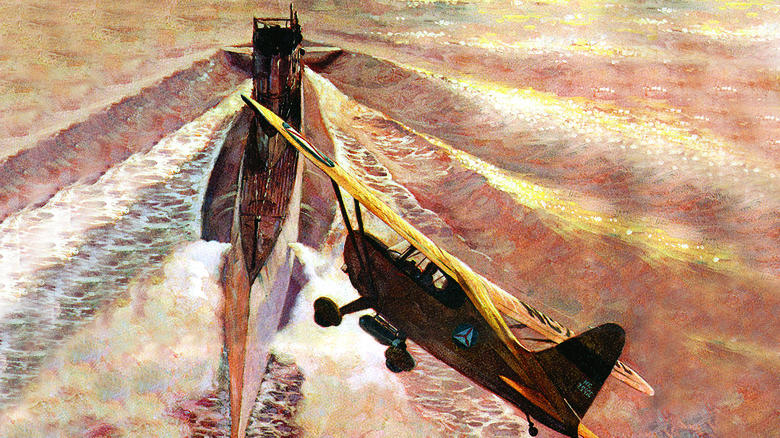

The Civil Air Patrol was born out of straight-up desperation. In 1942, German U-boats were torching oil tankers off America's Atlantic and Gulf coasts — sometimes only dozens of miles offshore. But the U.S. military was tied up overseas.

The solution? Hand the job to civilians flying their own airplanes. These weren't war machines by any means — they were mainly Fairchild light aircraft, flown by anyone Uncle Sam hadn't already drafted. Many women wore a Civil Air Patrol uniform to support the country. With just a compass, a radio, and a lot of guts, they flew out over the ocean looking for periscopes.

It sounds like a long shot, but it worked. The Civil Air Patrol spotted so many U-boats that the War Department eventually slapped bombs and depth charges under their wings. Yes, bombs on little single-prop planes. And they actually used them — attacking 57 submarines and credited with sinking two. Not bad for volunteers with no training.

Today's Civil Air Patrol is less about depth charges and more about data

After the war, the Civil Air Patrol was folded into the Air Force as its official auxiliary in 1948. Instead of combat, it shifted into three roles — emergency services, cadet programs, and aerospace education. Out went the bombs, in came the cameras. Now it's the country's top inland search-and-rescue force, handling about 90% of missions as directed by the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center.

And it's not just eyeballs out the window anymore. With radar analysis and even cellphone forensics, the crews can find a missing hiker or a downed plane before anyone spins up an engine. Case in point: February 2024, when a CAP radar team nailed the location of a crashed Marine Corps helicopter in brutal weather in just 30 minutes — directing rescuers to within 300 feet of the wreck. And when a plane disappeared in Alaska this year with 10 people aboard, the Civil Air Patrol sprang into action and tracked it until the wreckage was found floating on sea ice.

Beyond that, the Civil Air Patrol is first call for aerial images after hurricanes, floods, and other disasters. On September 12, 2001, a lone Cessna it operated became the only civilian plane cleared to fly over Ground Zero, photographing the destruction for responders below.

The Civil Air Patrol also is fixing America's pilot shortage

The most immediate mission is saving lives. But the lasting impact? Training new pilots. Aviation has a massive pilot shortage, thanks mostly to the wallet-destroying cost of flight training. The Civil Air Patrol is one of the groups trying to solve that problem. Every one of its 30,000-plus cadets gets five free flights in a powered plane and five in a glider. For the ones who get hooked (which seems like most of them), there are summer flight academies where teenagers can solo before they can legally drive themselves to the airport in some states.

The capstone is the Cadet Wings program, which pays for a Private Pilot Certificate. Some 400 cadets have earned their wings this way. But aren't drones sort of the future of this stuff? Possibly, but the Civil Air Patrol has that covered as well, with an extensive drone training program.

The pipeline seems to work. Roughly 10% of every incoming Air Force Academy class is made up of former Civil Air Patrol cadets. That's hundreds of new aviators who got their start flying with volunteers. Or as one Cadet Wings grad was quoted by CAP News: "That is 400 dreams that have come true."